In British Columbia, the Salmon Run Defines an Environment and its Culture

Article

In Canada’s westernmost province, Pacific salmon play an unparalleled role in their ecosystems and the heart of fishing communities that depend on them. In light of their declining numbers, preserving this species has never been more urgent. Here’s why — and how — Age of Union has stepped up.

Author

Daphne Rustow

Topics

Between its rainforests, mountain peaks, glacial lakes, and Pacific coastline, British Columbia (B.C.) has long been recognized as one of Canada’s most stunning regions. The province is also home to another natural wonder: the salmon run. This migratory event sees salmon returning to the rivers where they were born to lay their eggs before perishing shortly thereafter. If you know where to look, you might catch the river waters turn red in September and October as hordes of salmon make their final journey upstream, often travelling several thousand kilometres and fighting challenging waters to begin a new life cycle.

Age of Union has partnered with the B.C. Parks Foundation to preserve the Pitt River Watershed, a vital sanctuary and spawning ground for salmon in Katzie First Nation territory, as the species faces mounting threats from climate change and industrial development. Here’s what you should know about the environmental, cultural, and spiritual significance of salmon and the challenges they face today.

The role that salmon play in this part of the world, both environmentally and culturally, cannot be overstated. Salmon are critical to the wildlife, fishing communities, and greater ecosystems which depend on them — but climate change and industrial development present a growing threat to this species.

In the Fraser River, B.C.’s largest river and one of the world’s greatest salmon-producing waterways, more than half of the salmon species are in decline relative to their former abundance. Further north in the Skeena River, the province’s second largest river, Sockeye salmon returns are estimated to have decreased by 75% over the last century.

As a keystone species, salmon play a crucial role in the environment, and their disappearance would significantly impact the ecosystem. Over 130 species of wildlife, including eagles and bears, rely on them as a dependable food source. Additionally, the carcasses of salmon provide nutrients for freshwater ecosystems, serving as a nitrogen source for trees and fertilizing the soil. Improved water quality, reduced soil erosion, and the presence of other fish species are often observed in areas where salmon are found, underscoring their importance in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

Indigenous communities along the coast of B.C. heavily depend on salmon, with archaeological records showing that many permanent First Nation village sites were intentionally established near salmon-producing streams or rivers.

Today, salmon remains an essential source of physical and spiritual health for many communities. For the Secwepemc people, who live in the province’s southern interior, salmon often appear in legends, songs, ceremonies — and even in the Secwepemc language. The Secwepemc word for September translates to “time of salmon,” while the word for October means “time of spawning.” Similarly, the Lheidli T’enneh Nation and the Stó:lō Nation, who live near the Fraser River, also have deep cultural and linguistic ties to the fishing, processing, and eating of salmon.

Historically, First Nations communities have used sustainable fishing practices in an effort to preserve the species. For the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation who live on the West coast of Vancouver Island and who see salmon as a foundational element of the nature around them, salmon are almost exclusively captured upstream near spawning grounds to ensure that enough fish have completed the salmon run.

The decline in B.C.’s salmon population can be traced back to the European colonization of the province, when land use methods, agricultural practices, and the commercial trade market radically altered the fish’s habitat. Today, ongoing industrial development and climate change pose an imminent threat to the species. The introduction of flood control structures, such as dams, leads to disruptions in water quality and wildlife corridors. Additionally, the deforestation of shorelines contributes to changes in water temperature and exacerbates the probability of flooding and droughts. Rivers are very dynamic systems, and modern land development practices often threaten their inherent design in ways that aren’t always immediately perceptible.

By partnering with the B.C. Parks Foundation, Age of Union hopes to preserve a critical salmon sanctuary in the Pitt River Watershed. This ecosystem, home to waterfalls, hot springs, and wild salmon, faces mounting pressure from industrial development. With the designation of the area as a permanent conservation zone, Age of Union aims to protect its unique ecosystem and facilitate access of local Indigenous communities to previously privately-held land — in the hopes that salmon can continue to run for generations to come.

Topics

Article written by

Daphne Rustow

As a Content Producer for Age of Union, Daphne looks for the stories at the heart of our partner projects and finds the best way to bring them to life. She brings a decade of experience in documentary film, breaking news, and animation, working both in production and post. She is keen on finding compelling visuals and strong characters — and is particularly interested in the ethics of documentary filmmaking and content production.

Related

articles

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

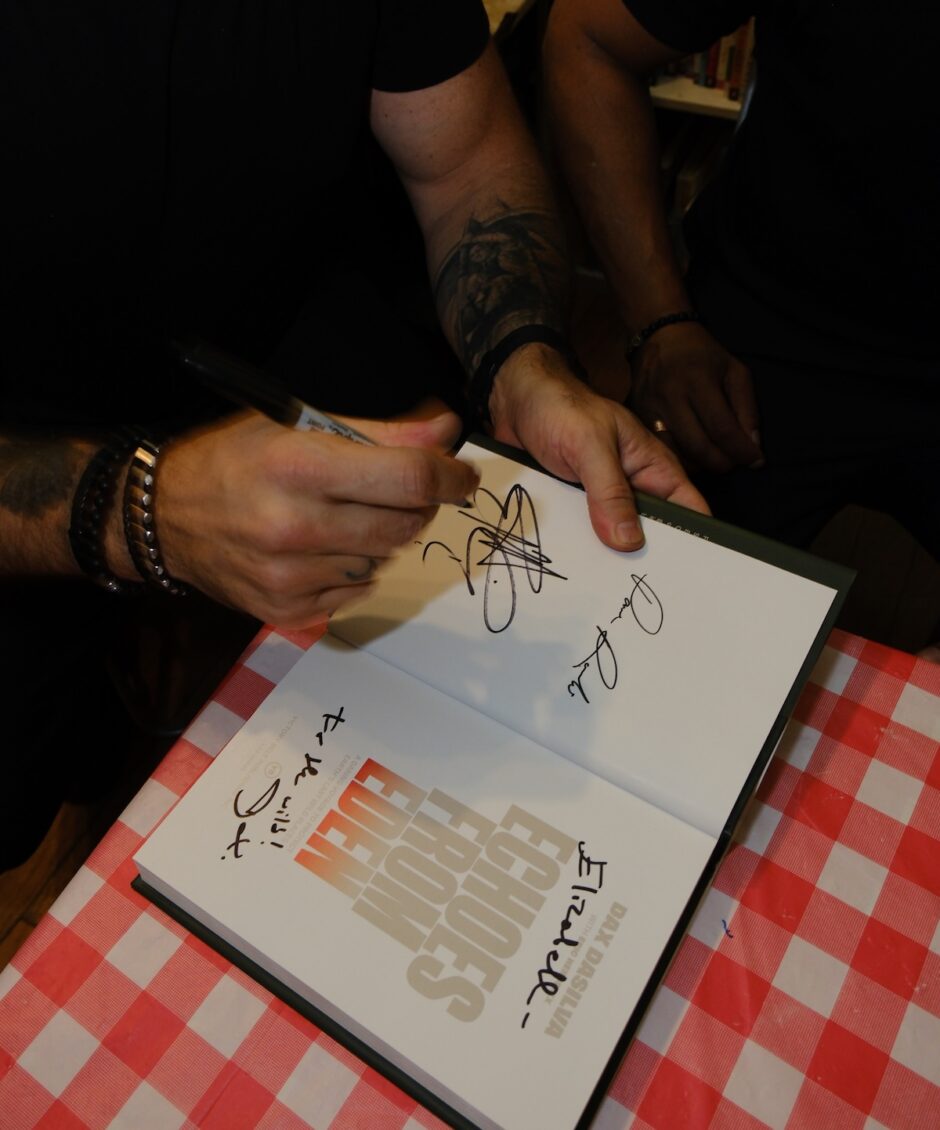

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film