How Apps Are Transforming Science and Conservation

Article

Smartphones, apps, and emerging online technologies are revolutionizing citizen engagement in active science, making conservation efforts more accessible than ever. Here’s a glimpse into the initiatives of Age of Union partners, such as the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Save Estuary Land Society, as they harness these tools to drive positive change.

Author

Jean-Philip Rousseau

Topics

“The app is called Carapace,” says Annie Ferland, project manager for the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC). “Carapace helps us collect turtle sighting information across the territory.”

It’s a beautiful Saturday morning in Montreal. The cloudless blue sky is filled with light. The sun is as radiant as the smile of the ten volunteers being welcomed on a quiet residential street. The location was kept secret until the very last minute because, even here, NCC has to remain mindful of poachers.

“You should use Carapace whenever you see a turtle,” says NCC Turtle Conservation Technician Simon Boudreault, just as a turtle coincidentally happens to make its way around the group.

Saving the Planet One Picture At a Time

Carapace, which means “turtle shell” in French, is a fitting name for a citizen science tool specifically developed to help shelter turtles from human activity.

Citizen science is a collaborative approach to scientific research that involves the participation of the general public in data collection, analysis, and problem-solving. It empowers individuals to contribute to scientific projects, expanding their reach and efficiency. In the case of biodiversity, citizen science enables anyone to observe, document, and monitor various species and ecosystems, providing valuable data for researchers and conservationists.

“You only need your smartphone or your camera,” Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) Montreal and Lower Laurentians Project Manager Annie Ferland says. With a pledge of $3 million from Age of Union, the organization is working to protect and restore key natural habitats along the river with restoration projects and initiatives like Carapace.

Ferland explains that by taking a picture and sending it along its geolocation data, any hiker or nature lover can act on the spot via the iNaturalist app or later through the website.

“I get an email with the picture and a dot on the map,” she says. “Then, we can confirm the species, what it’s up to, and more. We can get a lot of information from a [single] picture.”

Once the information becomes available, data takes centre stage, offering valuable answers to a plethora of questions. How many sightings have been reported? Where did they occur? Are there any critical nesting locations that require special attention? The aim is to determine the best course of action for protection by examining trends and shedding light on whether sightings are increasing or decreasing.

“The difference is quite substantial, whether it’s one student or 100 people reporting sightings,” Boudreault says.

Ferland and Boudreault are briefing volunteers on today’s operation: controlling the spread of the common buckthorn, an alien invasive species, within the nearby turtle nesting area. At this time of year, stumbling upon a reptile is quite likely.

“I didn’t even know there were turtles in Montreal,” says Katarina Rieder, a volunteer. “I wanted to help.”

“I definitely came here for the turtles,” adds Nour Habib, also giving her time.

Can Science Get Too Much Data?

At the other end of the country, Denise Foster, chair of the Save Estuary Land Society in French Creek, B.C, is managing another Age of Union-backed project in a different geographical setup. The eastern coastline of Vancouver Island bathes in the salty waters of the Strait of Georgia, facing the Rockies and the mainland.

“We did have a comment section on the form, and enthusiasm from the volunteers resulted in paragraphs of information,” Foster explains. “There’s a lot to process.”

The technological configuration is also quite different from NCC’s, but the input of citizen science remains just as essential.

“We have created an online form,” she explains. “It follows [scientific] protocol for reporting and documenting information on bald eagles and great blue herons.”

Since the beginning of the year, bird enthusiasts in the area have been enrolled to help monitor nest locations and bird behaviours. Phase 1 of the project took place over the winter, and Phase 2 is now in full spread.

“[Bald eagles and great blue herons] are laying eggs, and chicks are hatching,” Foster says. “It’s really an amazing time for citizen scientists to be out there.”

The data collected is processed by the dedicated team from Vancouver Island University. Once processed, the information is uploaded to databases used by governmental agencies. This is an essential step in the process that involves identifying nest locations and holds the potential for initiating area protection under the laws of the Canadian province.

“We have a lot of ongoing projects relying on citizen science,” Foster adds. “Insect, bat, and butterfly surveys, and so on.”

Citizen Time Is Money

Governments, non-profit organizations (NGOs), and scientists would be hard-pressed to gather such a vast amount of data at such a minimal cost. By involving more people in the process, conservation efforts gain an army of ambassadors, spreading the message far and wide.

“Citizen science can operate at a scale that would be otherwise unaffordable on the limited science funding available to ecologists,” says Adrian Forsyth, tropical ecologist and strategic advisor of the Andes Amazon Fund, based in Washington, D.C. “[It] is essential for engaging the public in understanding how the Earth is doing.”

“This is where you take action,” Age of Union Projects Coordinator Mariette Raina notes. “With these apps … you can have an impact by just documenting what you see around you.”

Back in Montreal, NCC’s Ferland concurs: “Sometimes, people are fatalistic, thinking that nothing can be done, but you can have a positive impact on nature by changing your habits.”

Grabbing your smartphone and documenting what’s around you is one easy way — and one that scientists and biologists will thank you for.

The citizen science revolution has already started, and it’s only the beginning.

Credits

Cover: Deborah Freeman

Picture 1, 2 & 3: Jean-Philip Rousseau

Picture 4: Mike Yip

Picture 5: Deborah Freeman

Picture 6: Mike Yip

Topics

Article written by

Jean-Philip Rousseau

Related

articles

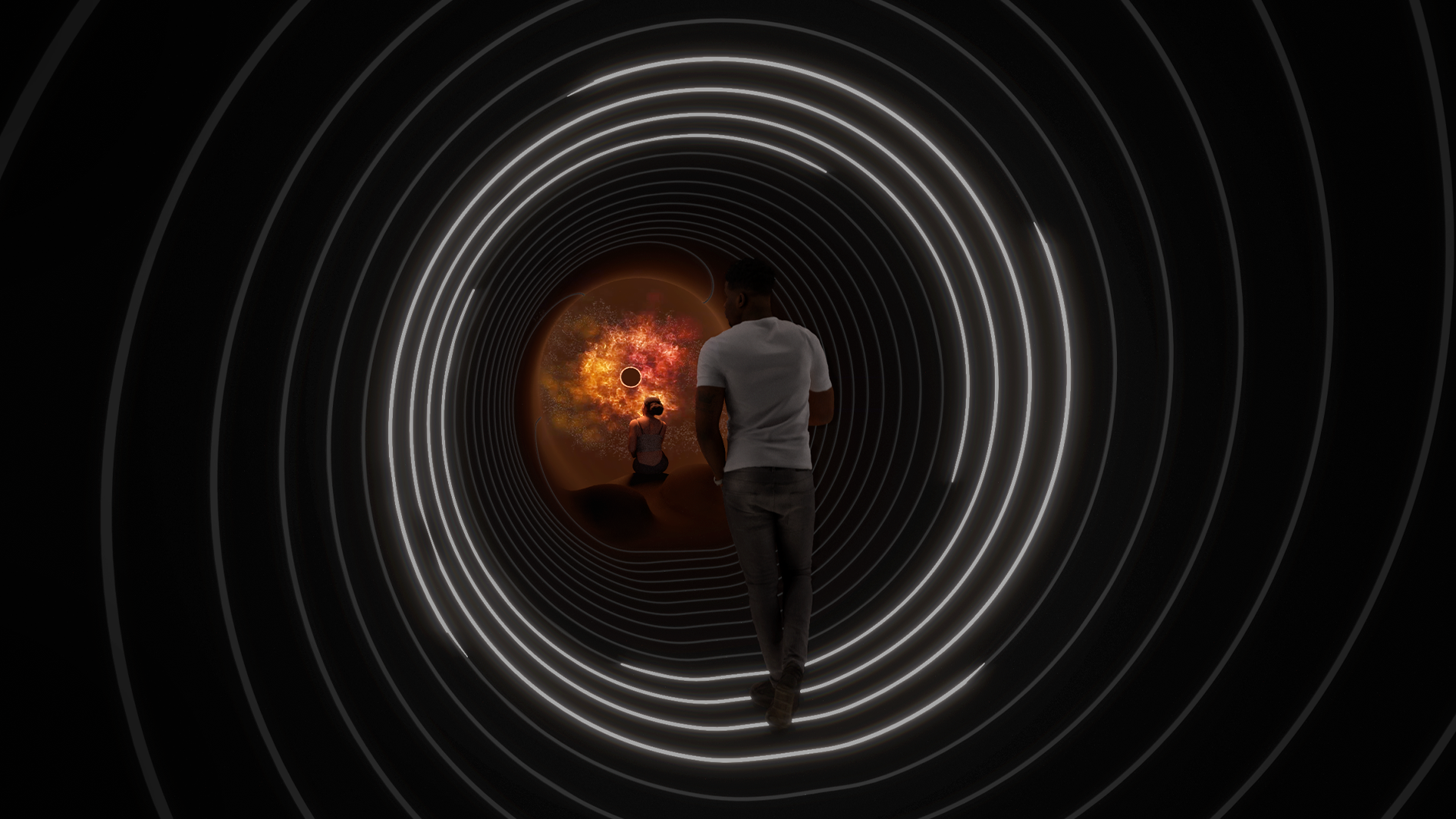

Black Hole Experience, Explainer

What Black Holes Can Teach Us About Nature and Spirituality

America, Film, News, Project

Age of Union Reveals New “On the Frontline” Episodes Featuring Kenauk Reserve’s Conservation Efforts

America, Explainer, Project, South America

The Braided Lives of Birds and Trees in the Western Amazon

Project

More articles

Black Hole Experience, Explainer

What Black Holes Can Teach Us About Nature and Spirituality

Black Hole Experience, News

Black Hole Experience Premieres at C2 Montreal

News

Age of Union Alliance Unveils The Black Hole Experience, a Mobile Immersive Exhibition and Reset for Humankind

News