Why Protecting Congo’s Ecosystem is Good for Both People and the Planet

Article

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, this initiative proves national conservation efforts and local communities can cooperate to protect both nature reserves and traditional lifestyles.

Author

Jacky Habib

Topics

The Congo Basin forest, spanning six countries in Central Africa, is the planet’s second-largest tropical rainforest after the Amazon. Located primarily in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), it spans roughly 1.6 million square kilometres and accounts for over a quarter of the world’s remaining tropical rainforest.

“Everyone knows about the Amazon forest, but not so much the Congo Basin forest. It’s overlooked, but it’s one of the most important forests that we need to protect,” said Mariette Raina, Projects Coordinator at Age of Union.

The Congo Basin, known as the “lungs of Africa,” is the world’s largest carbon sink, absorbing more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than the Amazon. Its protection is critical as the forest is vital in slowing down global climate change.

The forest is a diverse ecosystem providing food, water, shelter, and medicine for local and Indigenous communities. It is also home to various endangered wildlife species, including forest elephants, chimpanzees, and lowland and mountain gorillas. Half of the gorilla population in the Kahuzi-Biega National Park in the Congo Basin has been slaughtered by rebels, poachers, and illegal miners.

Due to factors including environmental degradation and climate change, the forest is at risk of deforestation, isolation of pockets, and the loss of ecosystems.

Since 2020, Age of Union has worked with the Forest Health Alliance and Strong Roots Congo to protect the forest and create habitat connectivity for endangered species by building and conserving a wildlife corridor, which also acts as a climate shield.

The partnership focuses on expanding the corridor, referred to as Kahuzi-Biega – Itombwe Corridor, to protect the great apes, and placing land management and conservation into the hands of Indigenous communities historically oppressed by conservation initiatives.

Tensions Between Protecting Nature Reserves and Preserving Community Lifestyles

In the 1980s, Congo’s Pygmies, nomadic hunter-gatherers, were expelled from their villages in the Congo Basin and forced to relocate without support when the government and international conservation organizations created a nature reserve, delineating 15,000 square kilometres and forbidding human activity, including hunting and foraging for traditional medicine.

Since then, many similar efforts to protect Congo’s forests have led to continued displacement of community members living in and around areas of interest, leading to violent, deadly clashes. Reports indicate that state-sponsored attacks in the name of conserving nature reserves in the Congo have included arson, sexual violence, and murder of Indigenous people to expel them from ancestral lands.

“For too long, community perceptions towards conservation and national parks have been largely negative, given the history of colonialism and displacement exacerbated by the national park system,” said Raina.

Partnerships Pave the Way to Sustainable Change

In an effort to shift this dynamic, DRC’s national conservation agency, which manages all national parks, Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN), met with Bakisi community members to discuss, document, and demarcate the boundaries between the Kahuzi-Biega National Park and the community’s forests.

In 2022, historical land titles were delivered to various communities for the first time in the region’s history, recognizing communities’ territories and protecting them from being evicted from their land.

Their cooperative efforts signify repairing the relationship between local communities and the national conversation authority and pave the way for continued cooperation to protect the forest and acknowledge community land rights.

“Land titles for Local Community Forestry Concessions are extremely significant because they are in perpetuity. The government can no longer allocate another title to these lands [such as] mining or forestry,” explained Dominique Bikaba, Executive Director of Strong Roots Congo.

Mining is a major industry in the DRC, which supplies approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt, used in laptops, phones, and electric vehicles. Mining companies have previously encroached on community land and forests, failing to consult with community members as per national laws. In addition, studies show that communities frequently clash with multinational mining companies over issues including land use, relocation, environmental pollution, loss of livelihoods, and human rights abuses.

“This [delivery of land titles] is a very important step in the process, but this is only the beginning,” Bikaba said. “The work now is to create sustainable management of the secured forest.”

Credits

Matt Brunette

Topics

Article written by

Jacky Habib

Related

articles

Project, South America

Puerto Nuevo Indigenous Community Secures Land Title After 25 Years of Effort

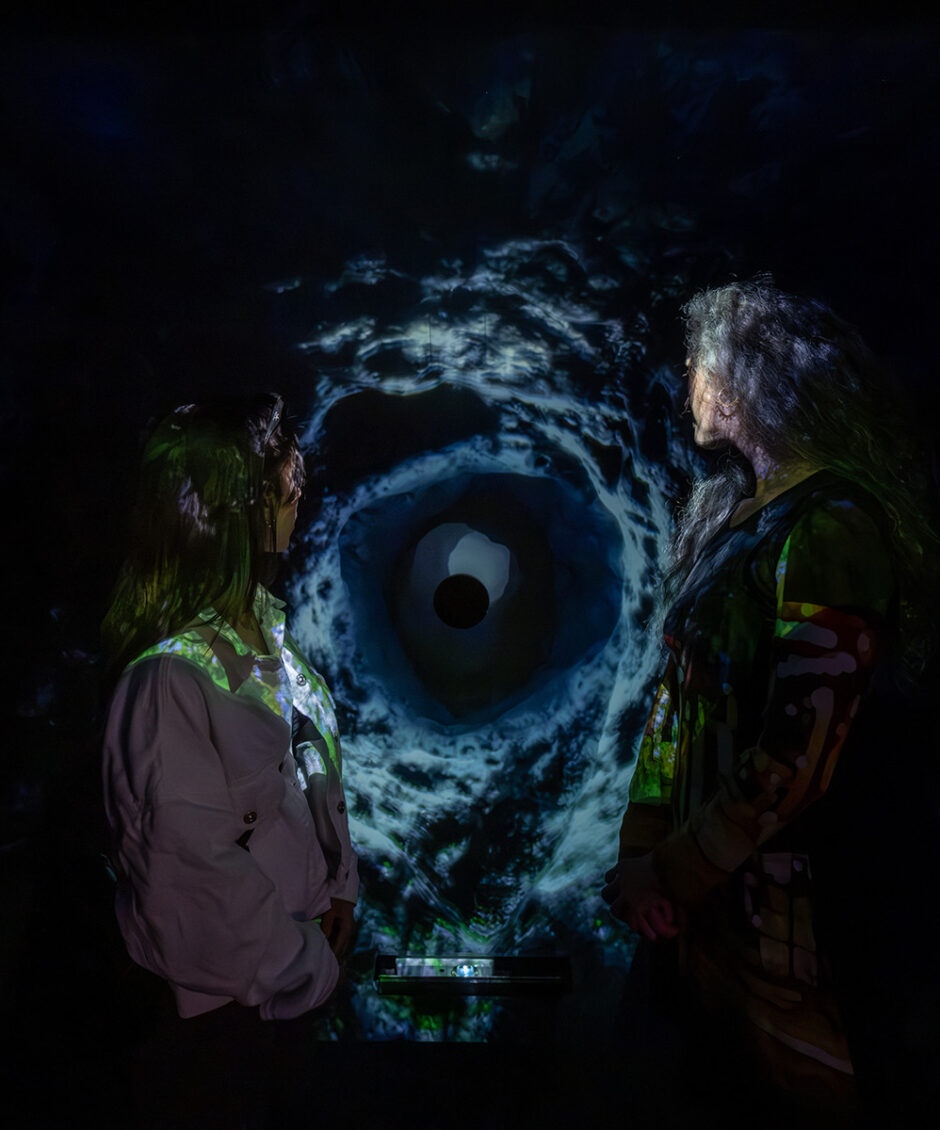

Black Hole Experience, Explainer

What Black Holes Can Teach Us About Nature and Spirituality

America, Film, News, Project

Age of Union Reveals New “On the Frontline” Episodes Featuring Kenauk Reserve’s Conservation Efforts

Project

More articles

South America

How Technology is Opening New Windows into Unseen Parts of the Wild

Black Hole Experience, News

Electronic Music Artist Jacques Greene Unveils Bespoke Track “Ligo” for Black Hole Experience at MUTEK

Project, South America

Puerto Nuevo Indigenous Community Secures Land Title After 25 Years of Effort

Black Hole Experience, Explainer