How Age of Union Helped Save a Threatened Forest in the Peruvian Amazon

Article

Each year, human-caused clearing destroys more of the Amazon Rainforest. In 2019, Age of Union teamed up with Junglekeepers to preserve it. In this article, Junglekeepers Founder and Field Director Paul Rosolie returns to see how the jungle is recovering years later.

Author

Paul Rosolie

Topics

The earth was smoking, so we had to walk carefully. Blackened trees were still glowing on the ashy ground, the tropical sun blindingly hot. Dax and I had walked through towering ancient forest to reach this spot, and so the contrast was shocking: what had once been dark green, jungle-shaded, moist, and lush with life was now obliterated to scorched earth. The trees lay blackened and smouldering. Wildlife was gone. As we walked, we could hear the snap and pop of fire but little else. Everything had been destroyed.

It was 2020, and we had come with the Junglekeepers team to investigate the front lines of the Amazon fires — specifically, an ongoing invasion into one of the crucial areas we had been working to protect. Long before Junglekeepers existed, local conservationists had been striving to protect this land and all the ancient trees and complex diversity of wildlife it held. Only during the pandemic, when everyone’s guard was down, the invaders moved in. First, they cut a football field worth of jungle. Then another. As Junglekeepers rangers and directors alike scrambled to respond, we faced a sudden reality: we were losing vast tracts of forest every day. We were losing the fight to protect what it is our mission to guard. As Dax and I walked shoulder to shoulder, we barely spoke, both stunned to silence to witness so much destruction. In those moments, I remember feeling hopeless and scared, like there was no way to stop it.

For context, fire in the Amazon rainforest does not happen naturally, but every year, we see more and more of it burn. In 2019, the Amazon Rainforest was burning so badly that it made international headlines. The burning Brazilian Amazon smoke swept over Sao Paulo, and the apocalyptic images went viral. For a few weeks, everyone was talking about it. But then the news cycle moved on. Humans have been burning the Amazon at alarming rates for over thirty years now, and the loss of old-growth forests is weakening the ability of the Amazon to function as a rainforest. There was hope when the fires of 2019 finally received some global coverage. But that hope faded the following year when the Amazon burned far worse, reaching catastrophic levels.

Many people think the Amazon fires are a natural occurrence — an understandable misconception given that some forest ecosystems do often naturally burn. But the Amazon Rainforest does not burn naturally. During much of the year, these forests are so thoroughly saturated that napalm couldn’t get them to light. No, the Amazon fires that we see ravaging Amazonia are human-caused. In the Amazon, forests are cut at the end of the rainy season and left to dry in the scorching tropical sun. This crucial step allows the trees to desiccate to the point of being burnable. Then, in the dry season, these cut forests are set ablaze to create farms and cattle pastures. According to Brazil’s space agency INPE, 3,358 fires were burning across Amazonia as of Aug. 22, 2022.

We hear about these things, but few people see them up close. On that day, we walked amidst the burning, felled trees, aware that what we were seeing was just one of the thousands of manmade scars that have been eating away at Amazonia (to date, we’ve lost roughly 20% of the Amazon Rainforest as a biome).

Dax sat beside Junglekeepers Co-Founder and Indigenous conservationist Juan Julio Durand as he negotiated with the invaders, speaking to them in both Spanish and local dialects to try and understand why they felt they had the right to cut this forest, which had been growing for centuries, and which he had been working to protect for over 20 years. Where had they come from? What did they want? The invaders were indignant and claimed ownership. They made it clear they weren’t going to leave. They said they were going to clear a lot more land. They had already cut and burned and hunted out over 15 acres. I remember leaving that day wondering: How far would this go? This could be the start of the end for our vision of protecting this river.

After that day, we knew we’d have to take serious action, and we began consulting international experts and lawyers and working around the clock to devise a strategy to assist local law enforcement in stopping the spread of this invasion. After all, the burning of primary forests is illegal. As is stealing land, killing wildlife, and trafficking cocaine or illegal timber. All of which were taking place during this invasion.

It took another year and a lot of long nights, last-minute Zoom calls, strategizing and stress — there were death threats, serious ones, made by the invaders on the Junglekeepers team. But eventually, we were able to bring law enforcement in to ensure that the invaders were brought out.

That was a year ago now. The hunting finally stopped, the chainsaws were silenced, and the ancient trees stopped falling. For a year, that land has been quiet. So we went to see. Was the clearing still as bad? Did we need to focus on reforestation or restoration? What had become of the huge scars that had been cut into the forest?

What we found was miraculous. What had once been burned wreckage was now bustling with new life.

In the year since the last of the invaders was removed, the forest had done an incredible job of healing itself. The clearings were no longer bare; in fact, much of what we saw was thick, with a new secondary forest cover that was over 10-metre tall in places. Cecropia and balsa wood trees had shot up. Bamboo was rampant. These pioneer species are already creating leaf litter on the new forest floor and making shade that will allow the fungus and vines to move. Gradually, the jungle is healing its wounds. We found ocelot tracks, deer tracks, peccary, and armadillo holes. There are signs of tayra (a giant weasel), tons of birds, butterflies and reptile life. As it turns out, the Amazon Rainforest is an expert at healing itself. As pioneer species like bamboo, cecropia, and balsa shoot up, the birds and bats carry seeds that will bring in various hardwoods. Deer droppings will sprout new saplings.

It could take up to 500 years for the ecosystem to fully recuperate, for there to be ancient trees and a full climax community ecosystem. But in the meantime, this secondary forest is a fantastic habitat for many species. This is proof of concept for the crucial work that Junglkeeepers can do with the support of Age of Union. For the first time, the local people of the Madre de Dios have the chance to protect their natural heritage. As we walked, JJ knelt and turned to me with wonder.

“Look!” he said. “This is a baby ironwood.” The tiny tree was not even a sapling, just a sprout barely up to his knee. But it’s a start. Centuries from now, that little sprout will have turned into a sapling, and the sapling into a towering giant, a skyscraper of life.

Seeing the regrowth taught me something. It reaffirmed that if we were not doing this work, this forest would certainly be destroyed. It also kindled what I had always hoped: if we can protect this ancient ecosystem, the jungle can endure some scars. We may have lost some crucial acres, but because we are covering most of the surrounding habitat, the forest will continue the endless march of life, and the churning speciation will continue for uninhibited millennia. And long after we are all gone, a great and ancient basin of life will continue to exist in an ever-changing world.

Credits

Mohsin Kazimi & Paul Rosolie

Topics

Article written by

Paul Rosolie

Paul Rosolie is an American conservationist and author. He is also the founder and field director of Junglekeepers. His 2014 memoir "Mother of God" details his experiences working in the Amazon rainforest in southeastern Peru.

Related

articles

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

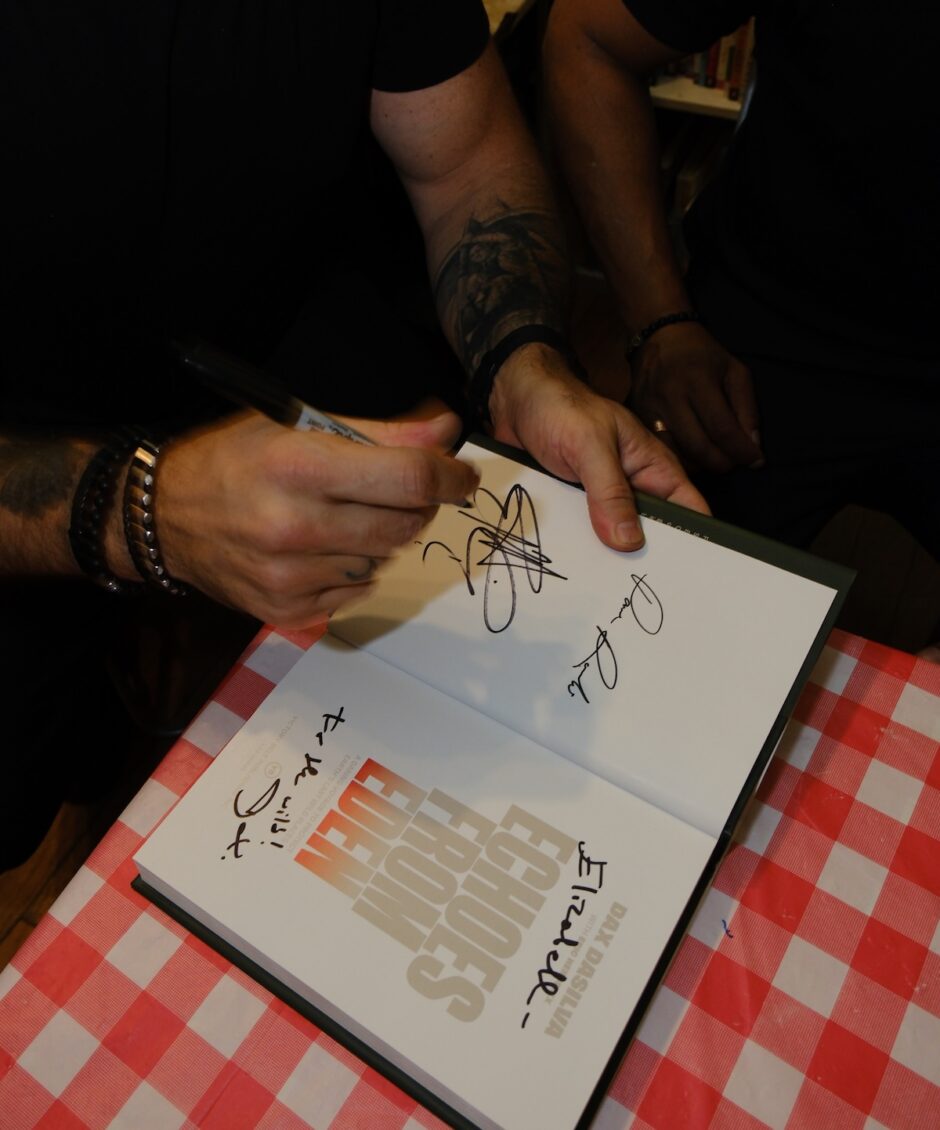

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film