A History of Transformations at the Age of Union Centre

Article

As it prepares to close its doors, we reflect on the impact of Montreal’s Age of Union Centre, tracing its transformation from a glass-making factory to a vibrant space for tech, art, and environmental activism.

Author

Lucy Fandel

Topics

The 12,000-square-foot building at 7049 St-Urbain in Tiohtià:ke/Montreal’s Mile-Ex neighbourhood, home to the Age of Union Centre since 2021, has at times been a home, a production space, a startup headquarters, and a cultural gathering place. With the Centre closing on March 16, the people who have transformed the vocation, vision, and literal walls of the place over the past decade are taking the occasion to reflect on the building’s multiple lives.

Since the building’s purchase by tech entrepreneur and environmental activist Dax Dasilva in 2011, it has served as the offices for Dasilva’s then-start-up Lightspeed, a gallery and production space for his arts organization Never Apart, and a central hub for the environmental alliance Age of Union that he founded in 2021. Innovators in film, tech, art, culture, and environmental action often overlapped amidst the space’s evolution, encouraging conversations across sectors and cultural communities.

For Dasilva, the building was nothing short of transformational. “It’s been all of my major projects … The building has been a big part of my life and identity.”

In a Neighbourhood of Makers and Margins

At the turn of the century, francophone Quebecers and European immigrants followed the tramway line 55 northwards on Saint-Laurent Boulevard to the city’s margins at the rue Isabeau, now known as Jean-Talon. They were attracted by the possibility of self-sustenance, often harvesting food in the fields and wood from nearby forests.

Throughout the 20th century, the area morphed from a sparse residential area into a zone of multiple uses as industrialization took root with textile, glass metallurgy, and other forms of production. In 1968, Leandro and Claudia Boriero incorporated their family glass-making business, Vitrerie Saint-Urbain, at 7049 St-Urbain, where they made windows and mirrors for regional buildings and businesses until 1995.

The present-day name for the neighbourhood, Mile-Ex, reflects the neighbourhood’s multifaceted and liminal nature, snuggled between the Mile-End to the south and Parc-Ex to the north. Despite exclusionary patterns of gentrification, the area still holds a mishmash of old industrial buildings, small businesses, tech companies, and residences. Artists have found places to explore and create, too. Among them are Karen Trask and Paul Litherland, who opened their gallery Produit Rien in 2019 in an old tofu factory on Marconi Street.

Acclaimed filmmaker Pierre Gendron first converted the Centre building from a factory into an artistic and residential space. Legend has it that caretakers told Sylvain Brochu, now Director of Operations at the Age of Union Centre, that the place used to house a pipe and plumbing manufacturer after the glass-makers, leaving behind a mix of industrial contaminants.

An extensive decontamination process was necessary to make the property eligible for residential use. Gendron then outfitted half the building for film production and the other half as his family living space with an in-ground pool in the garden. The small movie theatre he built at the heart of the home has remained in use with each successive occupant.

Lightspeed In the Wilds of Montreal

In 2011, Dasilva bought the building from Gendron for his company Lightspeed. The company, which employs over 3,000 people worldwide today, was a rising start-up just shy of 50 people at the time.

Upon visiting 7049 St-Urbain, Dasilva knew it would be more than just an office space. “It was just this dream space,” he recalls. “We wanted to be a destination employer. I mean, what company has a pool?”

Before finding the building, the company had burst through the seams of three consecutively larger office spaces, and Dasilva wanted a space to help the company grow. The building and Lightspeed transformed over the following four years, with desks multiplying through a place that was in a quasi-exotic location for visiting tech investors at the time.

“I think they felt like they found a gem, a treasure in the wilds of Montreal… where probably few of them had been, let alone invested in,” he said. When he invited Californian venture capitalists to visit, the ensuing investment triggered another unprecedented growth spurt.

With over 150 employees, desks crammed into every corner and spilling over in a patchwork of nearby rental offices, the company finally moved into their current home in the old Viger Train Station heritage building on Saint-Antoine Street, or as they call it, “the castle.”

Never Apart

Michael Venus, Executive Director of Age of Union Centre and Never Apart before that, remembers hanging out in August by the pool in the garden at Lightspeed when Dasilva brought up his hopes of creating a safe community-oriented space. He wanted to use the building to give back to the creative community when his company moved.

“I remember hearing Lori Anderson, Peter Gabriel, and Brian Eno were going to come up with an artist theme park, and that’s sort of where my mind went,” said Venus, an artist, filmmaker, and founding member of the House of Venus collective. He felt Canada needed a space with immersive artistic experiences — and he knew how to build it.

Venus recognized a common ethos from House of Venus that he carried to Never Apart. “We were very much do-it-yourself queerdios who created our own scene because there wasn’t one.”

After a few months spent planning and meditating on what the space could become, Dasilva launched the non-profit Never Apart in 2016 with Venus and Music Director Anthony Galati as a cultural and artistic gathering place focused on welcoming the LGBTQ+ community.

For Dasilva, it was a spiritual project that helped him recover from the intensity of Lightspeed’s ascent and offered him a way of supporting the city’s cultural community. He credits the city’s artistic fibre with museums and festivals such as Divercité and Black and Blue for inspiring much of his work at Lightspeed. The city’s artists and cultural workers reinforced his understanding of the positive social impact of creative gathering spaces.

Never Apart’s team generated a whirlwind of cultural programming, including performances, exhibitions, workshops, conferences, a seven-season online TV series, a web magazine, music productions, and legendary parties that attracted thousands of people. The embrace of diversity ran deep in the organization’s functioning, both in the people and the types of projects it took on.

For Brochu, the diversity-driven mission was both a source of pride and a deeply creative endeavour. He wrote in the 2020-2021 season booklet about diversity and creativity being a highlight of his job, underlining that the beauty of his role came from the breadth of collaborators and the diversity of logistical tasks it brought together.

“For any project to come to fruition, there must be people working in the shadows,” he wrote.

For him, this included doing everything from buying a lightbulb to greeting artists and managing exhibit openings.

Reaching success required inventiveness at every level, and the impact was far-reaching. Partnerships extended offsite with organizations in the city and events in cities such as Toronto and Los Angeles. Never Apart became recognized as an important springboard for emerging artists, often supporting first exhibitions or performances. Word spread. Venus remembered a slow night for a vernissage often meant greeting 800 people on a Thursday.

With each exhibition, people were invited to gather through events, discussions, and interviews, many of which remain online on the organization’s website. The encounters between people of different ages and backgrounds felt uniquely hopeful to the team at the time.

“I’m fond of the Legend Series that we did,” said Venus, referring to interviews and discussions in which Never Apart invited senior artists from the LGBTQ+ community to share their experiences with an all-ages audience. “It was a real intergenerational moment.”

The programming at Never Apart multiplied and expanded discussions around identity. Dasilva remembers the discussions accompanying exhibitions exploring Black diasporas and Indigenous Two-spirit communities as especially impactful: “Our idea of diverse experience exploded through people’s art. It wasn’t just exhibiting. It was experiencing other people’s worlds.”

Age of Union Centre

As with many cultural organizations, the pandemic wrought a devastating blow to Never Apart, particularly as a place whose impact depended on gathering together. The team noticed that the forced migration to online communication worldwide created a polarizing tone in the language used for societal discussions about identity.

As Dasilva and Venus searched to redirect the conversation positively, the emphasis on nature began to gain significance. “You know, there’s no arts and culture without a planet,” said Venus. The environment was already a core theme at Never Apart and central to Dasilva and Venus’s personal values.

Dasilva’s 2019 book, Age of Union: Igniting the Changemaker, served as the guiding manifesto for the environmental alliance and the transition from Never Apart to the Age of Union Centre, as his organization Age of Union Alliance donated $40 million to ten grassroots environmental conservation projects led by local and Indigenous changemakers around the world.

The metamorphosis of the Centre and its community-focused vision stemmed from a familiar approach for Venus. Like Never Apart and House of Venus, it anchored and provoked much-needed conversations in response to current cultural needs.

The first two years of the Centre’s operation were transformational, much like they had been for Lightspeed. Through visits and exhibitions, they enabled ongoing relationships to form with various Indigenous artists and curators, such as Adrian Stimson, as the global organization formed connections with environmental luminaries such as Jane Goodall and Leonardo DiCaprio.

In keeping with the desire to support encounters between local communities and international issues, the Centre hosted projects by Montreal-based artists in new media, such as Aude Guivarc’h, Kelly Nunes, and Melanie O’Bomsawim, and international conservation figures in conservation like Prince Hussain Aga Khan. Regular conferences, workshops, and guided tours also invited visitors to take an active part in conversations around sustainability in the hopes of inspiring people to get involved in the socio-ecological transformations of their own communities.

Dasilva hopes the building’s legacy will ripple through initiatives such as an upcoming Age of Union mobile exhibition. With the closing of the Centre, he envisions a “dispersal of environmental art energy” that will reach people in different contexts, from campuses to remote areas to city centres.

Reflecting on the legacy of the building, he said, “What the Age of Union Centre proved to me is the value of environmental art.”

Credits

Clara Lacasse and Ludovic Rolland-Marcotte

Topics

Article written by

Lucy Fandel

Related

articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

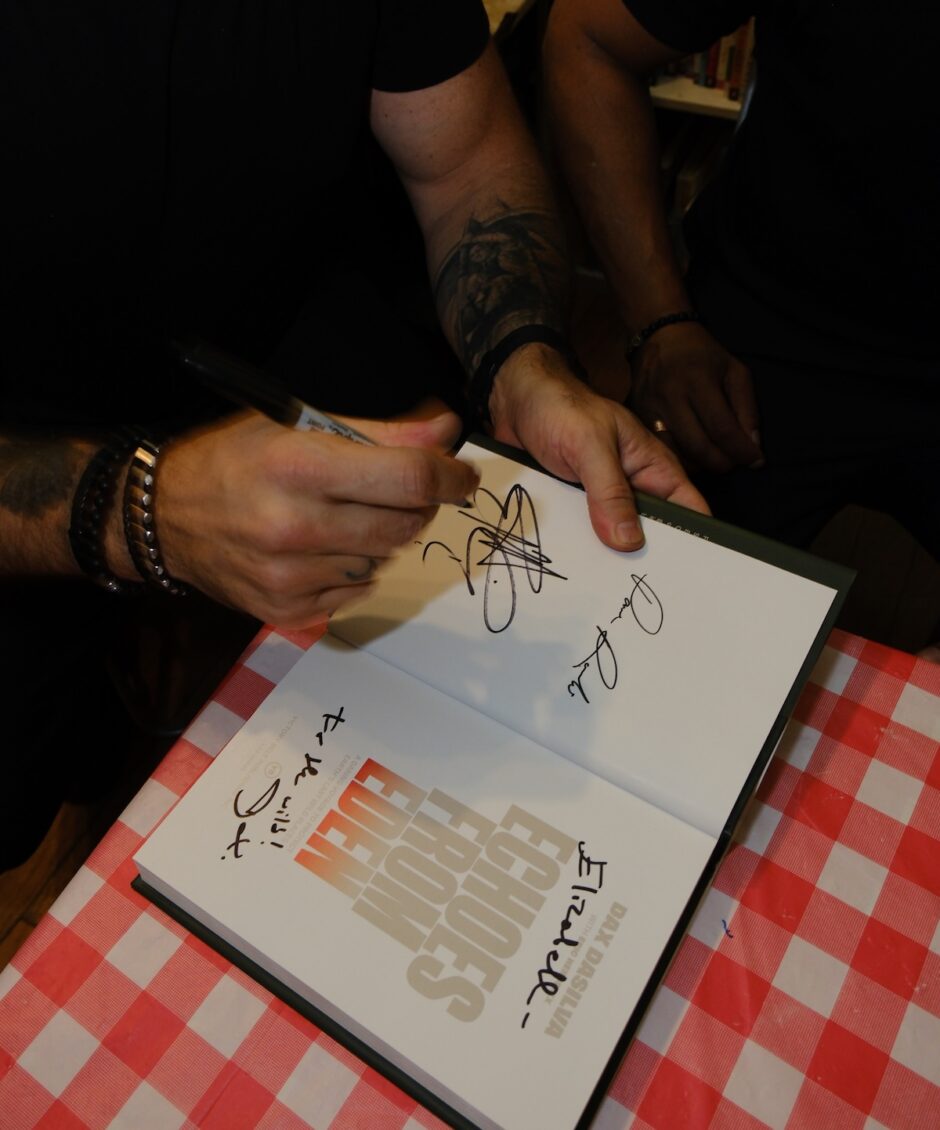

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film