Women of the Earth: Stories of Hope on International Women’s Day

Event

As a documentary filmmaker, I’ve witnessed the climate crisis rising around the world. I’ve seen firsthand how poaching and overfishing are depleting the oceans. I’ve driven through wildfires. I’ve spoken with people days after their homes were destroyed from a hurricane. Amidst all of these moments, it has always been women who reignite my hope.

Author

Sam Rose Phillips

Topics

Today, for Women’s Day, we take the time to honour how critical women are to the care and protection of this Earth.

Diversity is a powerful agent for change. I am continuously inspired by those who stand up for the planet through connection to lands, science, activism, art, and spirituality. Alone, each approach cannot sustain this planet for very long. Together, a profound shift becomes possible.

In celebration of this diversity, I wanted to share with you three women who bring great hope to my heart and embody this work from different perspectives: Alexandra Morton, biologist; Tiffany Joseph, young knowledge carrier of the Sḵx̱wu7mesh and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples; and Rebecca Benjamin-Carey, activist. I spoke with them this week on the importance of women in the protection of nature.

ALEXANDRA MORTON

“This is women’s work.” Alexandra Morton speaks these words into her phone without hesitation. “Deep in our core, we’re about the next generation, we’re about sowing the seeds and tilling the ground and providing the environment for survival, growth, and family.”

Alexandra has been called “the Jane Goodall of Canada” because of her 30-year fight to save British Columbia’s wild salmon. She’s a field biologist and activist who has done groundbreaking research on the damaging impact of ocean-based salmon farming. She has stood against the farms, and has been vital to the many legal and protest actions against the industry.

Referring to the First Nations-led occupation in the Broughton Archipelago, she continues, “The women stand ground. I really saw this during the occupation of the salmon farms, which went on for 280 days. The young, Indigenous women really held the ground there. They knew the importance of just being there, of putting their bodies there, of creating a home there. It is deeply women’s work. We have the capacity to stay in one place and see something through. And we have the advantage that is in our DNA. It’s an asset to be a woman, it’s a strength. We are built to bear extraordinary pain and to raise our children, which is such a slow and demanding process. So there’s a certain amount of structure that is just built into us that when we apply it to our planet, it fits so well. It’s so natural.”

As I listen to Alexandra speak about this innate strength, every single woman in my life comes to mind. If this truly is women’s work, then why does it feel as though women have been left out of the conversation for so long?

TIFFANY JOSEPH

Tiffany Joseph, a steward and educator from Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and W̱SÁNEĆ ancestry, grounds this question in historical truth, “Patriarchal worldviews of early explorers and colonizers feared the power of matriarchal societies. Their first strategy in stealing land was to take away power from women. The colonizer knew that they couldn’t steal land if women and two-spirit people had any power and authority.”

She continues to explain: “In our culture, people of all genders were leaders of families, ceremonies, in the economy, and in stewardship of the land. The colonial influence took that power and control out of women and two-spirit peoples’ hands and put it in the hands of men as much as they could.”

She goes on to share, “Today, most of my restoration and education work is with women and two-spirit people. When I’m working with young people, it’s uncommon for my projects to be with men, and I think it’s because women and two-spirit people are reclaiming the roles that always belonged to us. It’s a natural surge happening to restore balance to our societal and natural ecosystem.”

REBECCA BENJAMIN-CAREY

Rebecca Benjamin-Carey lives in the traditional territory of the Komoks First Nation, on Hornby Island. She has been part of great white shark research in South Africa, sea turtle and coral reef conservation in the Caribbean, and patrolling for illegal shark fishing on the high seas. Today, her focus is on ocean conservation in British Columbia and she’s on the board of Conservancy Hornby Island.

Rebecca writes to me, “I feel it’s important to have people from all demographics represented in conservation, because we’re all stakeholders in the earth and all come from different experiences that need to be respected when making decisions for change. Women are such powerful and complex beings, who throughout their life end up having to overcome endless obstacles and develop an amazingly strong sense of self and determination in order to be successful in whichever arena they’re in. I see such an obvious link between the obstacles women face with simply trying to exist and the challenges that come with trying to reverse generations of damage done to the environment. It’s this inherent understanding of overcoming obstacles that make women so important in conservation.”

She continues, “The phrases that we usually hear in conservation are ‘no, that’ll never happen,’ or ‘no, that’s going to take too much work.’ Speaking as a woman of colour, it doesn’t make any sense to me. Understanding the experience of the obstacles other women, BIPOC, and LGBTQIA2S+ people have overcome to be where we are now, makes it even harder to accept those words. Big Change is possible and we’ve seen it. To me, there is nothing that can’t be done. There’s only whether or not you’re willing to do what it takes to make it happen.”

WOMEN, HEALERS OF THE EARTH…

Women have an innate capacity for sustainability. It’s in our bones to nourish and keep the beings around us alive. On this thread, Alexandra echoes, “The art of endurance is a female thing. That’s the only superpower I have. People will say to me all the time, ‘Oh, I’m just an average person. So I can’t.’ And I’m like, Hey, I’m not super anything. But I have endurance. And that is a female trait.”

And so where does this endurance come from? After listening to these three women, and considering my own resilience, two sources rise to the surface:

The first is the connectivity and farsightedness of women, of understanding who came before us and who we may help ahead. Tiffany lights up, “I have a responsibility to share my gifts. When I was a young person feeling daunted by living through life in this colonial world, I remembered my responsibility to future generations. I remembered that if I loved what was taught to me so much, then I could help bring as much of that into the world as I could, because that’s what my elders did. And if I loved everything that they brought into this world, I want to do the same.”

The second source is the inextricable bond between women and the lands. Tiffany upholds, “After many harms created by colonization, where they were so threatened by Indigenous women’s voices and power, they had to take everything they could to make us submissive. Because once you took away our power, then you could take over the land. So us stepping into our own power, asserting what’s ours, will bring back the strength of our people.”

Each of us carries our own unique way of stepping into our power for the better of the world around us. Nonetheless, Alexandra, Tiffany, and Rebecca seem to agree there is one non-negotiable.

Rebecca offers from experience, “I think we as women have to remember to stand up for ourselves as well as the environment. If we don’t, we end up getting burnt out and the world misses out on the fantastic impact women can have on healing the earth.”

Alexandra takes this one step further to say, “It is not selfish to take care of yourself. If you can’t breathe, and sleep, and go do the things that wind you down, you’re just not going to make it. And you’re not going to make the difference that the world requires right now. So my advice to women is don’t lose that thread. That love and care and affection that we offer to others, you have to turn it on yourself, too. You definitely rob yourself of your power if you don’t take care of yourself, and we need to be powerful now, to try against the odds. Find your ground and stand on it. Because the Earth is made of all these little ecosystems that are pressed together. Any positive influence you have on the ecosystem that you’re in is going to affect the others around you, and it is there where you have the most power.”

Once again, I am filled with hope in the presence of women sharing their truths and their gifts. Here’s hoping you are, too.

Topics

Article written by

Sam Rose Phillips

Sam Rose Phillips is a filmmaker, photographer, and writer based in Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ Territory, what is currently known as Ucluelet, British Columbia. She focuses her lens on human-wildlife stories and their cultural significance to coastal communities. Sam specializes in off-grid, remote storytelling both from land and on the water, spending the first 5 years of her career as a one-woman film crew. Framing narratives alongside collectives like Conservancy Hornby Island, Sea Shepherd, Stand, North Coast Cetacean Society, Clayoquot Action, and Cetus Research & Conservation Society, has instilled in her a dedication to integrating truth and hope into the same conversations. Her words, images, and films are published by Save Our Seas Magazine, Salty at Heart Journal, CBC’s The Wild Canadian Year, and Outdoor Photography Magazine. She is currently directing a documentary about coexisting with wildlife.

Related

articles

Project

More articles

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film

Environmentalist and Executive Producer Dax Dasilva Celebrates World Premiere of YANUNI at the 2025 Tribeca Festival

News

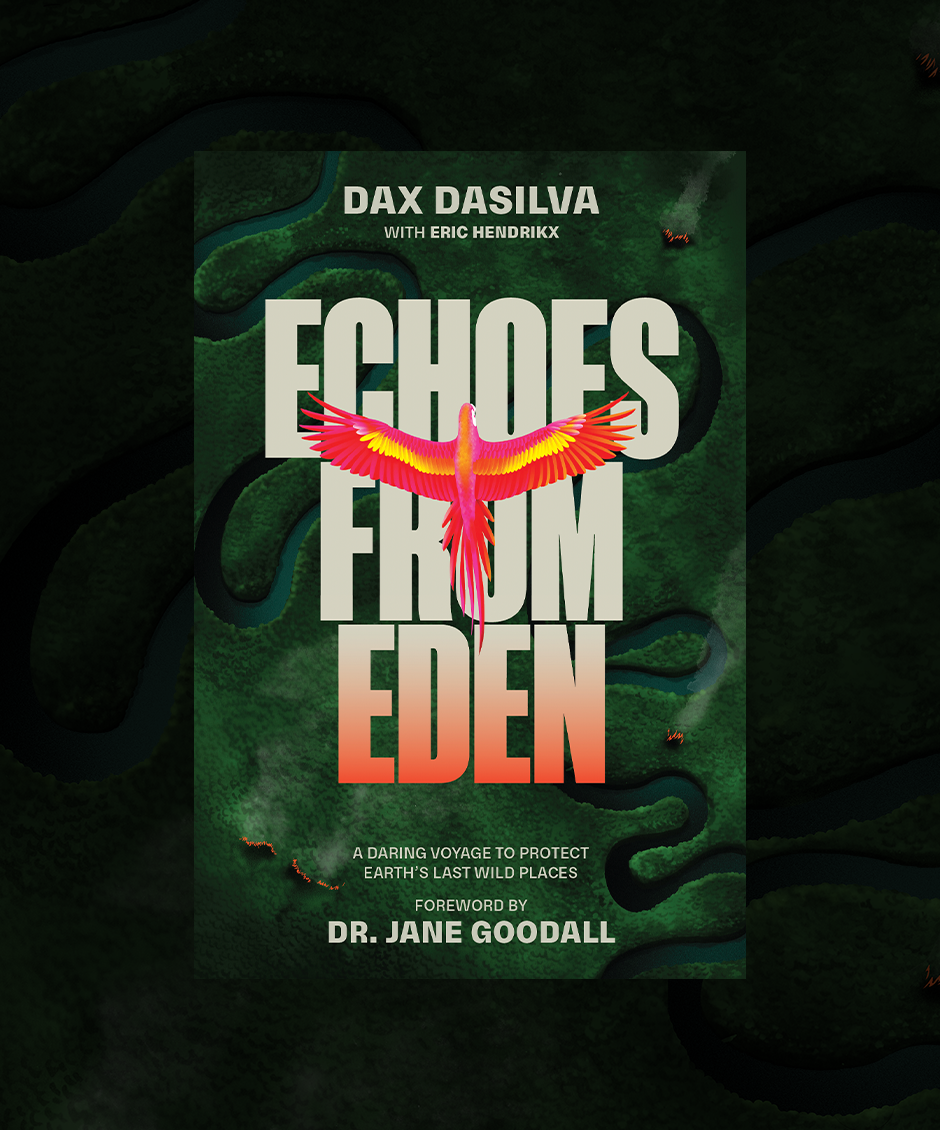

Tech Entrepreneur and Environmentalist Dax Dasilva Announces New Book Echoes from Eden As A Call to Action to Protect the Planet’s Vanishing Ecosystems

Africa, Film