Why Junglekeepers Champions Conservation in Peru’s Biodiversity Capital

Article

Discover the beauty and wonder of the Madre De Dios region through the eyes of Paul Rosolie. In this new series of articles, the Junglekeepers Founder and Field Director will provide fascinating insights into the Amazon’s treasures while documenting conservation progress in the region. Supported by a $3.5 million pledge from Age of Union, the organization aims to preserve Peru’s biodiversity capital.

Author

Paul Rosolie

Topics

Behold the Earth: as you drift in on South America, you’ll notice a vast and sprawling swath of green in the upper portions of the continent. As the Earth rotates, you can see the sun glistening on the veins running through the green—golden rivers winding like the capillaries of some great lung. Rivers, like the branches of the tree of life, spread out across the great basin of rainforest and grassland. This is the Amazon Rainforest.

The “Save the Rainforest” slogan has almost become a cultural cliché, but it exists in our consciousness for a reason. Once covering almost 15% of the Earth’s surface, rainforests now barely make up 6% of our planet’s surface and are home to 50% of the terrestrial species. These regions are rich with complex ecosystems of flora and fauna, including ancient trees, rare and endangered species, and undiscovered medicines. Despite the threat of endangerment, they remain thriving habitats for various Indigenous cultures. The deep forest serves as a sanctuary where they can flourish and be protected.

While most of us know that the Amazon rainforest is the largest contiguous rainforest ecosystem on Earth, what many people don’t know about the Amazon is how it was formed.

Around the time of Gondwana, Africa and South America were connected. Flowing across them both was a tremendous proto-Congo River system that started in the East and flowed West across Africa and what is now South America to drain into the Pacific. When the continents began to drift apart in the late Jurassic, the great river was broken in half, leaving Africa with only the upper reaches, which would later become known as the Congo River Basin.

Over the next 130 million years, South America drifted away from Africa, forming the Atlantic Ocean. The low-lying riverbed that had once filled from the Congo became filled with salt water until the continent jammed into the Nazca Plate — a geological giant that halted the drifting landmass and spiked the Andes Mountains out of the Earth, blocking the westward-flowing river. For a few million years, the entire Amazon Basin was nothing more than a massive inland sea; the stagnant, continent-sized swamp gradually desalinized and turned to freshwater. The slow transition is why many saltwater creatures adapted to freshwater. Today, more than twenty species of freshwater stingray probe the riverbeds of Amazonia, along with pink river dolphins, manatees, and others. When an ice age caused sea levels to drop, the Amazon swamp began draining into the Atlantic. The Amazon River was born. Such was the start of the river system as we know it today. In the hot equatorial climate and abundant moisture, the jungle flourished.

With that established, let us float over stone mountains which loom over the western limit of the Amazon. Here, the towering stone incisors and the snow-capped steeples of the Andes Mountains send glacial meltwater charging into the lush tropical cloud forests of the Andes, which then cascade down into lowland Amazonia. This meeting of the Andes–Amazon interface creates one of the world’s few “megadiverse” regions, a term dubbed by the United Nations Environment Program’s (UNEP) World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC). It is, by all measures, the greatest proliferation of terrestrial life, not only on Earth now but ever. To our knowledge, even in the entire fossil record, there have never been so many species of plants and animals concentrated in such an area.

This is the region in which Junglekeepers works.

Today, it is a lushly forested corner of the world where vast tracts of wilderness remain, threatened by wild bands of illegal gold miners, loggers, and narco-traffickers. The swamps are still soupy thick with species unknown to science and giant endangered black caiman — a crocodilian capable of reaching lengths of 18 feet. There are still green anacondas — the largest snake on Earth — piranha, jaguars, spider monkeys, harpy eagles, giant anteaters, over 1,600 species of hardwood trees, 1,500 species of butterflies, and roughly 700 species of birds. If you’d like to make yourself dizzy, just think about the untold tally of species of ants, spiders, and dragonflies and that up to 50% of the life in a rainforest exists in the canopy. Entire species whose lifecycles take place without ever touching the ground. A towering kingdom that we, as humans, have had very little access to.

Why, you might ask, would anyone choose to work in such a remote, dangerous, difficult-to-access part of the planet?

The answer can be found in how remote, little studied, and gravely threatened the Las Piedras River truly is. It’s a watershed that was hardly visited even a decade ago. The only historical writings of the river before the modern era only warned that it was a region dense with violent tribes and a place of which rubber tappers and explorers should stay clear.

Flowing through the heart of Peru’s Madre de Dios, the Las Piedras River is the region’s longest watershed. The vast primary forest cover makes this river a sanctuary for the superlative biodiversity in the surrounding national parks, such as Alto Purus, Bahuaja Sonene, and UNESCO World Heritage Site Manu National Park. All the science, study, care, and curation that lead to these world-renowned protected areas has led to the Madre de Dios being known as “the biodiversity capital of the world.” And yet the Las Piedras, the heart of the region, has been devastated by logging, land clearing, and illegal gold mining.

Twenty-something years ago, an Indigenous conservationist, Juan Julio Durand (JJ), and his partner at the time, were the first people with the adventurous spirit and wild grit to think even of beginning a small ecotourism venture deep in the folds of the remote river. These were the seeds of conservation sewn to the wild river. At that time, however, it was relatively peaceful, and JJ and his team had to travel for two to three days by boat to even reach the site of their little eco-research station. “Back then,” JJ says, “the forest was so wild, so quiet, you could go for days and days and see no one. It was just so wild. Like God, he had just made it and left it.”

But in 2009, when an offshoot of the Trans-Amazon highway connected the outside world to this previously isolated Garden of Eden, everything began to change. Since then, we’ve seen many of the towering ancient trees fall. We’ve seen an explosion of extractive hardwood logging and more and more land grabbing for illegal activities. By 2013, the Las Piedras River was changing rapidly. The signs are clear on a satellite image search: You can see the forest before the road, the forest with the road, and how the clearings around it begin to spread and metastasize as illegal invasions ramped up.

The forest, its wildlife, and the Indigenous communities living in it are in extreme peril as these changes occur — but positive change is happening. In the coming months, I will share some of the incredible work that the Junglekeepers team has begun. We believe this is a chance to protect something wild, authentic, and pure before it’s too late. It’s a journey that has always been Indigenous-led, gradually coming to involve people from all over the world, and it has only been possible with the crucial support of Age of Union. Now it has grown into a sincere, inspiring effort to mitigate illegal logging, save endangered species and ecosystems, and build a brighter, safer future for the threatened Indigenous groups who live along this wonderful river.

Credits

Photo 1: The Andes Amazon Fund (Instituto del Bien Común and credited to Jorge Galván)

Photo 2: Declan Burley

Photo 4: Paul Rosolie

Topics

Article written by

Paul Rosolie

Paul Rosolie is an American conservationist and author. He is also the founder and field director of Junglekeepers. His 2014 memoir "Mother of God" details his experiences working in the Amazon rainforest in southeastern Peru.

Related

articles

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Africa, Project

Inside the Fight to Protect Gambian Artisanal Fishermen and Biodiversity From Industrialized Fishing

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

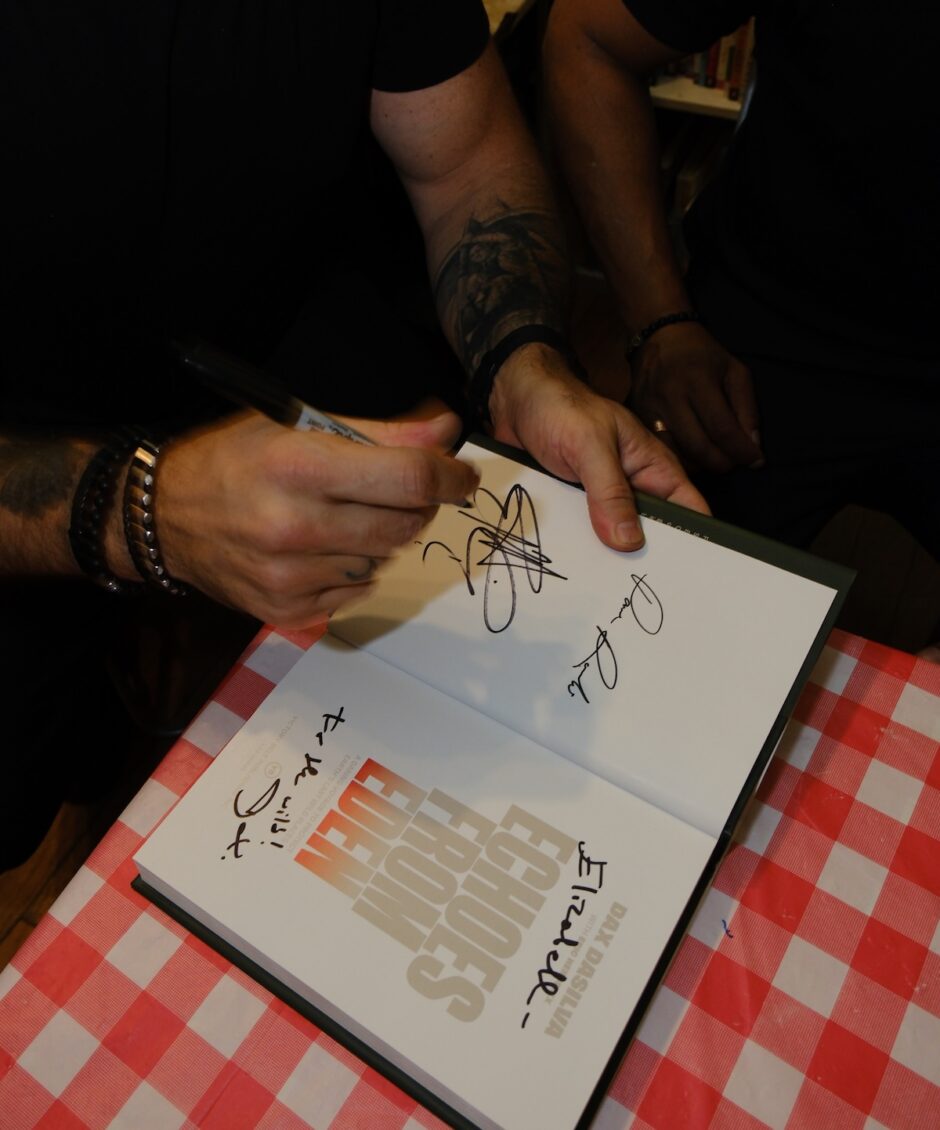

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film