The Clay Licks of the Amazon Rainforest: A Hidden Haven for Wildlife

Article

Junglekeepers Founder Paul Rosolie describes the fascinating world of colpas, areas in the Amazon Rainforest where minerals, particularly salt, leach out of the ground. These patches of land are frequented by a diverse array of wildlife, making them a natural meeting place for predators and prey. Through the use of camera traps, scientists were able to capture the secret life of Amazonian animals and shed light on the complex microenvironments of the rainforest.

Author

Paul Rosolie

Topics

People don’t realize how varied and complex the microenvironments inside the Amazon Rainforest truly are.

When you walk through the Amazon, as a tiny human beneath the towering canopy of ancient, 150-foot-tall trees, you are wholly cut off from the wildlife in the branches and vines that never so much as touch the forest floor: Birds, lizards, snakes, frogs, epiphytic orchids, bromeliads, mosses, lichens, and entire insect communities of ants, termites, wasps, bees, and many more.

The Amazon Rainforest is a patchwork of terra firma forest, floodplain, Pantanal (wetlands), and stunning bamboo forests. But in the western Amazon, where the Las Piedras River flows, where Junglekeepers focuses our efforts on the protection, preservation, conservation, and long-term future of the environment, there exists a marvel of the modern ecological reality that could shock even the most seasoned naturalist: colpas.

When the locals refer to colpas, they describe a place in the forest where minerals — most often salt — are leaching out of the ground. These areas can be beside a stream where the water has eroded the earth exposing salt-rich clay, or they can be in the footprint impression where a large tree has fallen, its roots lifting the earth and exposing the nutrients below. Colpas also form on the riverbanks where the charging flow of the current erodes the earth, exposing vast colpas which are frequented by parrots, macaws, monkeys, and other wildlife.

In 2006, when I first came to the Las Piedras River, I was working as a research assistant with local naturalist Juan Julio Durand, who has been exploring colpas his entire life. Juan Julio — or JJ, as we call him — has libraries of natural history contained in his mind. He can name most of the 600+ bird species that inhabit the region; he knows the tracks, the calls, the smells, and the medicinal plants. All of this and so much more are the result of growing up in the jungle, often barefoot, around his father, uncles, and brothers — loggers, hunters, farmers, trackers, shamen. It was JJ who first showed me the colpa that would change my view of the forest forever.

Even though there are hundreds upon hundreds of colpas hidden along the forests of the Las Piedras, this one was always and unanimously referred to as the colpa. It sits beside a winding forest stream, about two hours from the Las Piedras Biodiversity Station, which JJ owns and operates. When we first visited the famed hotspot of the forest, tracks were everywhere.

“Here are the tracks of brocket deer. Red. And over here are peccaries.” JJ was looking down, machete in hand, eyes illuminated and hyper-focused with calculation. “Look at this! This is Spix’s Guan track, and that is the giant armadillo. Such a big tapir!” Because all the animals come for the salt, it becomes a meeting place — all the animal trails lead here. And because all these animals are always visiting, the predators come, too. Look, here’s an ocelot….” JJ trailed off and began walking on all fours, studying the soft earth. “There’s a puma…”

Then, he turned to me: “And look, a jaguar!”

A few years later, we returned to the colpa with just two camera traps. Our aim was simple: to put out the cameras and see what we could get. Camera traps are an important tool in conservation: they allow biologists to capture, monitor, and study wildlife populations. In the Amazon, the greatest natural battlefield on earth, everything has adapted to be camouflaged, silent, and always avoid predation. A human in the forest is large and smelly — our detergents, shampoo, conditioner, deodorants, and often copious bug spray are blaring alarm signals to most wildlife. This means that when you walk through the jungle, even in the wild and richly-populated areas, it’s easy to go without seeing much life on the ground. But, as we were about to learn, this isn’t because it isn’t there.

We set up the two camera traps and left for a few weeks. Over that time, I returned regularly to check that the cameras hadn’t been tampered with. Over the years, I’ve had cameras harassed by peccaries, crushed by tapirs, splashed by mud from the driving rain, and even had spiders build tiny webs just over the camera’s lens, making the entire contraption useless. There’s nothing worse than returning to a camera trap and finding that it didn’t capture anything for one reason or another.

But that December, both camera traps worked, and they gave us insight into the secret life of Amazonian animals that would receive global attention.

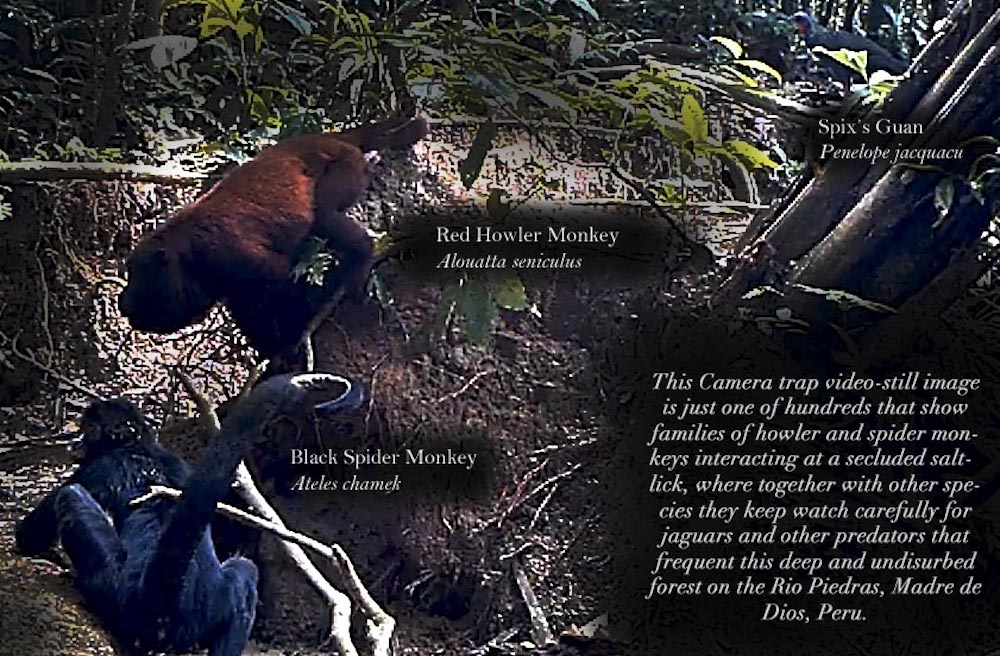

In just four weeks, the cameras recorded more than 2,000 videos of dozens of species. We were able to see interactions between howler monkeys and spider monkeys on the ground, peccaries nursing their young and foraging, massive Brazilian tapirs clopping through the mud with their babies — and, of course, in between these larger animals was an assortment of agoutis, paca, armadillos, squirrels, guans, trumpeters, and so many more.

Just as JJ had predicted, the colpa was also alive with the prowling, hungry eyes of the predators. Cats came in surprising regularity. The ocelots looking for small game. Slender pumas (Panthera concolor) stalk the outskirts and scent the earth. And then, of course, there were the jaguars — big males, young subadult males, and females — all circling through the colpa on their long patrols of the forest, sniffing out the next meal, learning habits of their prey.

The footage captured on-site went on months later to be awarded at the 2013 United Nations Forum on Forests for its rare insight into the secret workings of the Amazon and its glimpse of an unseen world that we, humans, are not a part of.

Now, in 2023, with support from Age of Union, Junglekeepers is launching a far larger and more comprehensive camera trap study of the wildlife of the Las Piedras. It is the braiding of Indigenous knowledge, field biology, and technology to provide vital data on exactly how superlative the richness and diversity of the river is. Though it is too early to say with scientific certainty, all indications are leading scientists to believe that the Las Piedras River may hold the greatest mammalian diversity in the Amazon Basin.

Credits

Cover: Mohsin Kazmi

Photo 1: Stephane Thomas

Photo 2: Paul Rosolie and Stephane Thomas

Topics

Article written by

Paul Rosolie

Paul Rosolie is an American conservationist and author. He is also the founder and field director of Junglekeepers. His 2014 memoir "Mother of God" details his experiences working in the Amazon rainforest in southeastern Peru.

Related

articles

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Africa, Project

Inside the Fight to Protect Gambian Artisanal Fishermen and Biodiversity From Industrialized Fishing

Project

More articles

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film

Environmentalist and Executive Producer Dax Dasilva Celebrates World Premiere of YANUNI at the 2025 Tribeca Festival

News

Tech Entrepreneur and Environmentalist Dax Dasilva Announces New Book Echoes from Eden As A Call to Action to Protect the Planet’s Vanishing Ecosystems

Africa, Film