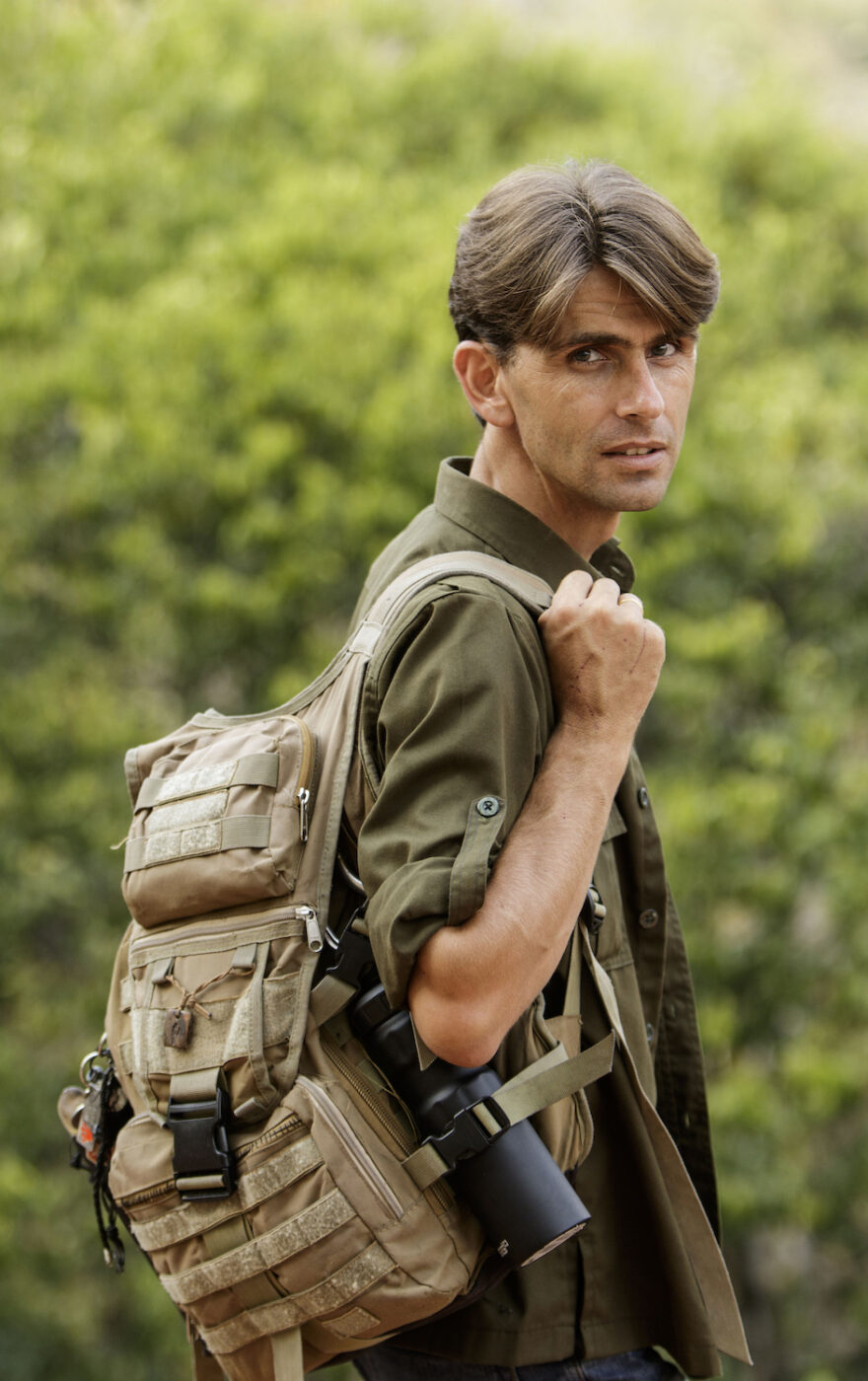

Why This Advocate Left France to Pursue a Lifelong Mission of Protecting Gibbons in Indonesia

Article

Age of Union spoke to Kalaweit Founder Chanee about his journey from France to Indonesia and how protecting gibbons became his lifelong mission.

Author

Cédric Varial

Topics

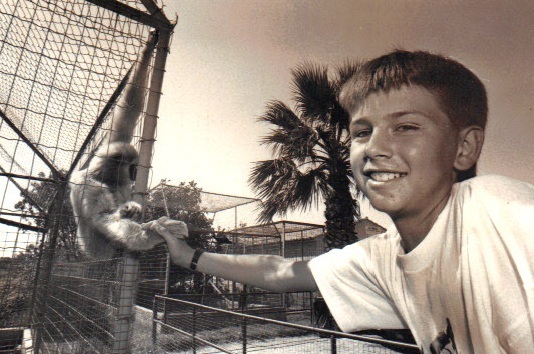

Chanee’s extraordinary journey began in 1991 at the Fréjus Zoo in his native southern France. “Of all the monkeys I saw in cages that day, the one that struck me most as a child was the gibbon and the sadness I saw in their eyes,” Chanee recounts 30 years later.

At age 12, he asked the zoo director for permission to spend his free Wednesday afternoons studying gibbons, a great ape virtually unknown to the general public.

“I spent five years observing gibbons every Wednesday, studying their behaviours and communicating with them. I eventually made suggestions to the Fréjus Zoo and other zoos to improve the animals’ well-being, and I helped form pairs of gibbons between French zoos. Nevertheless, I knew in my heart that this was only a stepping stone to my life with the gibbons.”

Drawing on years of observation, Chanee published his first book, “The White-handed Gibbon,” in 1997 at age 16. The critically acclaimed book introduced him to the general public and attracted the attention of French actress Muriel Robin.

“‘If you want to go to Asia to save gibbons, I will help you and fund your trip,’ Muriel told me on the phone. It was incredible. A few months later, I left for Thailand to spend three months camping in the forest among the gibbons. During this initiatory trip, I realized I could put aside everything I thought I had learned in zoos — the forest was another world altogether, and that’s where I had to act,” Chanee adds.

This experience also made Chanee realize that saving gibbons meant going to Borneo. An ecological disaster of enormous proportions was unfolding on the island: more than two million hectares of forest were being cleared to make way for palm oil plantations.

With Muriel Robin’s continued support, Chanee travelled to Borneo a year later, in 1998, and initiated the first gibbon conservation program with the Indonesian authorities in Jakarta. It would take a year of negotiation before the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed, and Chanee could legally receive animals in her first center. The Kalaweit Foundation was officially launched in September 1999.

“When you come up with solutions, implement structures that don’t cost the local authorities anything, take an interest in a species that nobody is doing anything about — compared to orangutans, for instance — and put a practical spin on active conservation, the chances of being told no are slim,” Chanee explains.

Hands-on action alongside local Dayak, with visible and concrete results and a commitment that extends well into the future, is paramount to Kalaweit.

“Most foundations that go to Borneo develop programs over 3 or 5 years and then leave. That’s not enough — sometimes, it’s not even worth it. My involvement here is personal. I came to protect and save the gibbons 25 years ago. I am still here. I came to stay.”

Over the past 25 years, Kalaweit has opened three centers in Sumatra and Borneo and rescued more than 2,000 animals: gibbons, of course, but also siamangs, bears, macaques, crocodiles, binturongs, reptiles, and birds. Kalaweit has also released hundreds of gibbons into the wild — a multifaceted challenge for all involved.

“Releasing gibbons is very complicated because you have to find forests where there are none. These primates are extremely territorial; any gibbon released among others of its species would be killed within days,” explains Chanee. “Plus, many of the gibbons in our rescue centers are unsuitable for release: 25% have human diseases like hepatitis, many are physically disabled, have been maimed due to deforestation or poaching, and others are psychologically traumatized. Seeing gibbons in our aviaries pains me, even with the knowledge that I have rescued them. I want to see these gibbons free in their natural habitat — and to do that, I have to protect the forest, plain and simple.”

Chanee’s new strategy is for Kalaweit to acquire forest plots, allowing the foundation to go beyond taking in injured gibbons or gibbons from illegal captivity, a widespread practice among wealthy families and high-ranking government officials who always end up abandoning them. Chanee understands the need to act upstream.

Kalaweit started its activity in Sumatra in 2010. A short viral video allowed the foundation to raise $100,000 in 15 days to acquire and protect 100 hectares of mountain forest, where many gibbon troops were already living. This instant success had the most extraordinary repercussions: eight years later, three tigers, an animal not seen in the region for decades, returned to the protected forest. “We underestimate nature’s resilience,” says Chanee. “Just freeze all human activities, stop disturbing wildlife, and ecosystems will restore themselves. We could be in for some big surprises.”

Results like these prompted Age of Union to support Kalaweit. Thanks to the non-profit’s $800,000 donation, 1,500 hectares of Borneo’s Dulan Forest are now under Kalaweit’s protection. As such, the gibbons and all other animals which inhabit the forest are now permanently protected from deforestation and poaching.

Chanee uses the Dulan Forest as a case study in his latest book. Published in 2022, “Hâte d’être à demain” outlines the need for local action in partnership with local people and authorities and the importance of involving everyone in conservation efforts.

“An Excel spreadsheet won’t stand up to chainsaws or prevent poaching. Things happen in the field. With daily patrols on horseback and by paramotor or seaplane, our continued presence ensures real protection. It also reinforces the necessary bond of trust with the local Dayak people. They guide us in our actions. After all, the Dayak know this forest better than anyone,” explains Chanee.

“Hâte d’être à demain”… looking forward to tomorrow, indeed! But for Chanee, the book’s strength lies in asking the following questions: If I were 12 today, would I want to get involved? If I were told repeatedly that the world was doomed, would I have the courage to do something as a young person? Where can the next generation find inspiration?

“I don’t think you can find inspiration in the dreariness of those who ponder the planet’s future and are not in the field,” he says. I’ve been out there for 25 years and see what needs to be saved daily. That’s what motivates me. Suppose I can save one monkey today; great. Suppose I can protect a few more hectares… even better! And that inspires people: the positives, big and small actions, and concrete projects. There is no end to hope when you see how much can be done to save what’s left.”

Twenty-five years after he built his first hut in the middle of the forest with four wooden boards and a Kalaweit sign, Chanee continues to inspire all those who cross his path with his insights and values. He still has the same publisher, Presses du Midi, and Muriel Robin is still like a second mother to him. Followed by the BBC and major French TV channels, he has millions of followers on YouTube and more than 1,600 monthly donors worldwide.

“I am where I wanted to be when I was 12. I still work, write, publish, and push forward. It has inspired a lot of people and brought about substantial change. You could say I wear many hats, including that of a family man. And it’s these values that I pass on to my 13 and 20-year-old sons. Every day, I tell them to put on their Kalaweit hats to become superheroes in the forest and save gibbons.

When he first visited the Fréjus Zoo 32 years ago, young Aurélien Brulé had no inkling he would change the course of so many lives. His own, first — he became Chanee (Gibbon) during his first trip to Thailand — but also that of thousands of gibbons, countless wildlife, and the forest itself.

Topics

Article written by

Cédric Varial

Related

articles

Caribbean, Profile, Project

This Rising Trinidadian Leader Is Paving the Way For Youth and Women in Conservation

Caribbean, Profile

Grammy-Winning Musician Régine Chassagne’s Inspiring Journey Towards Transforming Haiti’s Neglected Communities

Project

More articles

Black Hole Experience, Explainer

What Black Holes Can Teach Us About Nature and Spirituality

Black Hole Experience, News

Black Hole Experience Premieres at C2 Montreal

News

Age of Union Alliance Unveils The Black Hole Experience, a Mobile Immersive Exhibition and Reset for Humankind

News