The Braided Lives of Birds and Trees in the Western Amazon

Article

Junglekeepers Founder and Field Director Paul Rosolie shares how the ancient shihuahuaco trees form the foundation of a complex ecosystem, supporting countless species in the Amazon rainforest. With illegal logging on the rise, conservation efforts highlight the urgent need to protect these vital natural resources.

Author

Paul Rosolie

Topics

Recently, I observed a pair of macaws flying over the Amazon rainforest canopy. Red-and-green macaws (Ara chloropterus) are monogamous, meaning they mate for life, and this pair was on their way home for the evening. In the evening sunlight, the red and bright blue wings of the macaws were vivid against the jungle’s green shadows. The two birds landed in the branches of a great tree, its branches towering above the rest of the forest. They found a small hole, a unique nest, that they entered.

This observation confirmed the dependency of macaws on the large trees within the ancient forests of the Amazon. Red-and-green macaws don’t build nests like some birds. For them, safety from harsh weather and protection from predators is crucial to raise a healthy baby. As such, they rely on these great ancient trees so much that they nest virtually nowhere else. Studies and local observations have shown that macaws predominantly nest in shihuahuaco trees.

The shihuahuaco tree can reach heights of over 60 meters (196 feet) and ages of more than 1,000 years. Many of the trees that are over 1.2 metres inside the Junglekeepers reserve are estimated at more than 1,200 years old.

It’s hard to imagine that a seedling shihuahuaco tree was standing there in the forest for most of the historical events we could name easily. World War I, World War II, the painting of the Sistine Chapel, the founding of Oxford University, and many more. Our grandparents, great-grandparents, and most of recorded human history took place while that tree stood quietly in the vast jungle.

Other species that live on shihuahuaco trees include leaf-cutter ants, termites, wasps, various lizards and snakes, frogs, monkeys, kinkajous, frogs, and more birds than could fit in this paragraph comfortably. Shihuahuaco trees are akin to biological skyscrapers, hosting a diverse range of species. Because they tower above the canopy, harpy eagles nest in the tallest branches of trees that stand out above the canopy, using them as lookout points.

Macaws are attracted to the shihuahuaco trees for nesting, seeking out the cavities left by fallen branches. Due to the limited availability of these nesting sites, only about 20% of macaws can reproduce each year. Macaws may use the same nesting hole for hundreds of years, showing their close connection to the trees. This relationship is crucial, as these trees support a wide range of species in the ecosystem, but in the Peruvian Madre de Dios, where Junglekeepers works, the future of these ancient trees has become a point of concern.

Between 2010 and 2012, the Trans-Amazon Highway was completed, stretching across South America. This road enables travel from Sao Paulo on the Atlantic coast, through the Amazon, to Peru, and over the Andes to Lima. It marked the first time in history that a land-trade route opened the Amazon’s interior to Asian markets, increasing the demand for tropical hardwood.

The completion of the new highway granted unprecedented access to vast, previously untouched areas of the Amazon. Satellite imagery clearly shows the transformation: dense jungle regions have been dissected by roads, agricultural lands, and deforestation. In Peru, this development has led to a notable rise in illegal logging, targeting valuable woods such as mahogany, Spanish cedar, and, recently, shihuahuaco.

Local landowners, who have concessions designated for Brazil nut harvesting, have also contributed to this degradation by selling the rights to their timber trees to loggers. A few decades ago, cutting a tree with wood as impenetrably dense as a shihuahuaco would be near impossible, but more recently, chainsaw technology has improved. Today, chainsaws equipped with diamond teeth are widely accessible, allowing loggers to not only fell shihuahuaco trees but also process them on site. By the time the wood is transported downriver to Puerto Maldonado, it can be stacked and hidden among legally harvested wood, making illegal timber difficult to detect.

Tatiana Espinosa, a Peruvian forestry engineer, founded ARBIO, a non-profit organization (NGO) whose mission is to protect these ancient trees. According to Espinosa, the current rate of shihuahuaco extraction isn’t sustainable.

“In addition to the slow growth rate, it has a very low recruitment rate — there aren’t enough young trees to replace the adults being cut,” she said.

A study found the same in the Manu area, west of Madre de Dios. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) data sheets indicate that Diptery micrantha and Diptery ferrea are critically endangered and vulnerable, but Peru’s National Forests and Wildlife Service (SERFOR) still does not list them as threatened.

“It’s unacceptable that our government has been keeping the scientific evidence from the public, which clearly shows that urgent action is needed,” Julia Urrunaga, Director of the Environmental Investigation Agency’s (EIA) Peru program, said. “Regulating the trade in Shihuahuaco under CITES will help our country in the fight against illegal logging and corruption. Those in the industry who are already operating legally and sustainably will benefit and have nothing to fear and should support the proposal.”

In a way, the damage to the Amazon’s ecosystems can be compared to taking rivets out of a plane’s wing. Initially, missing a few rivets might not seem critical, but over time, removing more can weaken the wing and risk collapse. Similarly, the loss of ancient trees disrupts the forest’s complex web of life, essential for numerous species’ survival.

On a recent night in the forest, I ventured off the trail to examine the base of a notably large shihuahuaco tree. In the beam of my headlamp, I could see numerous vines, bromeliads, mosses, lichen, and even cacti growing on the great old tree. Bright green seeds were spread around the tree’s base, drawing dozens of fruit-eating bats. I’ve only seen this behaviour a few times: bats carrying shiny shihuahuaco seeds in their mouths, weaving through the night. Sometimes, as they passed, they’d drop these oval-shaped seeds near me, seemingly sharing their feast.

Standing by the tree, smiling, I watched this dance, dodging seeds, amazed by yet another link in the shihuahuaco’s web of life.

Credits

Cover: Paul Rosolie

Photo 1: Mohsin Kazimi

Photo 3: Stephane Thomas

Photo 5: Paul Rosolie

Topics

Article written by

Paul Rosolie

Paul Rosolie is an American conservationist and author. He is also the founder and field director of Junglekeepers. His 2014 memoir "Mother of God" details his experiences working in the Amazon rainforest in southeastern Peru.

Related

articles

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

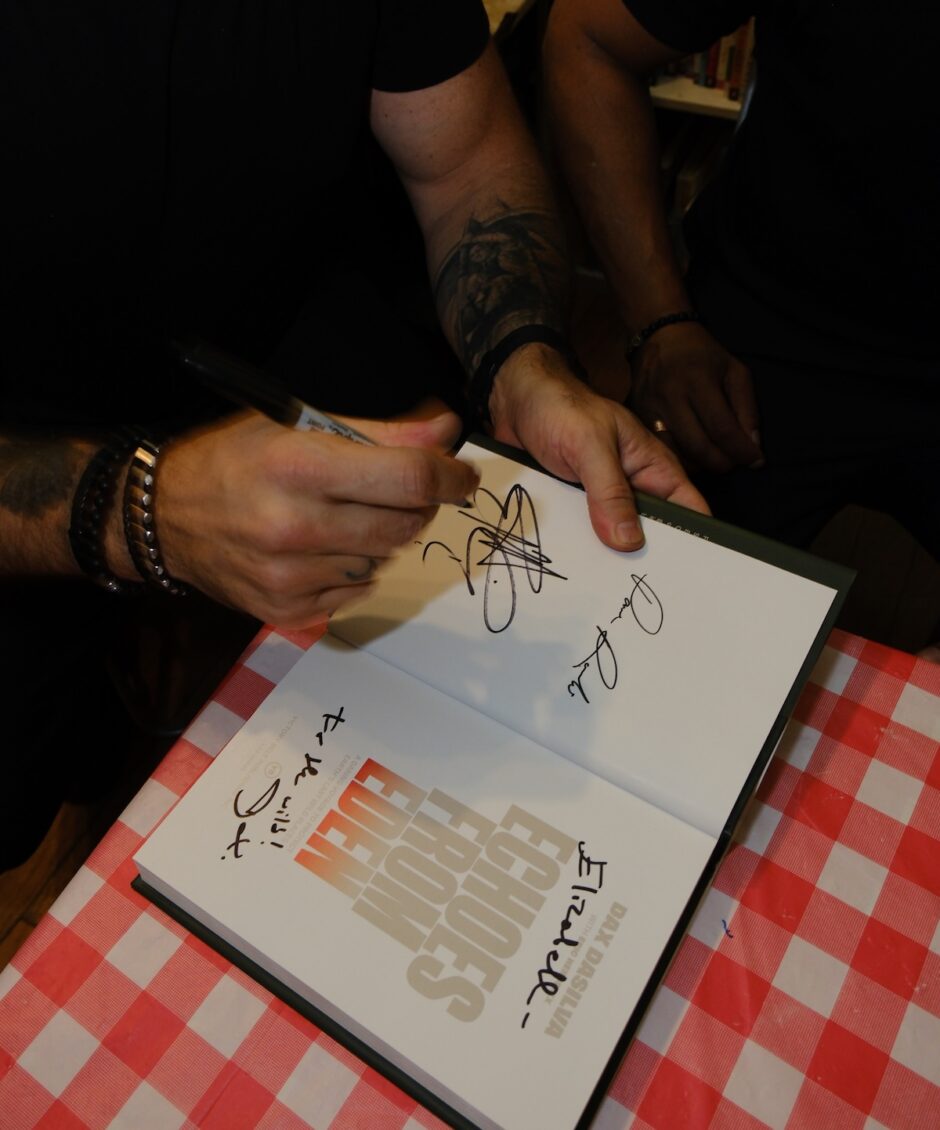

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film