Leatherback Turtles Face Existential Threats. This Trinidadian Group Fights for Their Future.

Article

Supported by Age of Union, the Trinidadian community organization Nature Seekers has transformed the fate of leatherback turtles through relentless on-the-ground conservation work.

Author

Joe McCarthy

Topics

In some years, the sargassum around Matura Beach in Trinidad is so dense it looks like a field of grass. For leatherback turtles, these massive algae patches act as maritime barriers, slowing or outright preventing trips to the shore where they lay eggs during the mating season. And it’s a problem that could get worse as climate change intensifies and global water temperatures rise, further fueling the expansion of algae.

Getting rid of the sargassum is no easy task, but Nature Seekers, an environmental nonprofit in Trinidad, deploys teams to deal with the problem. This could mean getting rakes to delicately clear the beach and shallow waters, taking care to minimize how much sand is lost, or it could require more drastic interventions.

“When necessary, we have a trailer that we put sargassum into and move it further back into open waters,” said Adrian Wilson, research officer at Nature Seekers. “It’s all about getting the nesting area clear.”

Getting the nesting area clear — and safe and comfortable — has been a top priority for Nature Seekers since its founding in 1990. The small, community-based organization, funded primarily through grants, tourism support, and community commerce initiatives, was formed to protect the leatherback turtle, which is currently listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Initially, poaching was their primary concern.

“For our employees, most of their parents would have been poachers, they would have eaten leatherback, they would have eaten the eggs,” Wilson said. “It was a normal thing. Back in the 1980s and early 90’s, about 50% of the nesting turtles were slaughtered nightly. Some of them were just killed for the fun of it, I guess. Some of [the poachers] would sell the flippers, so you’d find turtles that had no flippers and some that had chop marks on their backs or sides. The eggs are generally used in a punch that’s said to be an aphrodisiac.”

The first members of Nature Seekers had to change how people who lived near Matura Beach viewed turtles. They embarked on educational campaigns to inform communities about the importance of turtles and how the species was becoming endangered and could die out unless poaching ended. They also lobbied the government to create punishments for poaching, and actively guarded turtle nests and fought off poachers. This unglamorous work eventually earned broad respect and led to the end of leatherback poaching in the area.

Since the 2000s, a new crop of challenges has emerged, causing Nature Seekers to expand its scope. Thanks to a $1.5 million pledge from the Age of Union in 2022, the organization has been able to grow its team, pay higher wages, and set the seeds for future economic sustainability.

In particular, the funding will allow Nature Seekers to improve its data collection so it can better understand the health of leatherback turtles and Matura Beach more broadly. A newly acquired drone lets the team monitor larger sections of the beach, while more and better-trained staff will help with on-the-ground data gathering, measuring, tagging, and weighing turtles, counting eggs, and monitoring overall health.

This expanded capacity enables Nature Seekers to confront other threats facing the turtles, such as flooding and beach erosion. In recent years, rising sea levels and increased precipitation have inundated parts of the beach and nearby nesting areas. This both limits the potential range of turtle nesting sites and can sweep away existing nests.

With more team members patrolling the beach, more turtle eggs can be recovered and protected.

“We’ve built these artificial hatchery boxes that we fill with sand from the beach,” said Wilson. ”When we find eggs that are nested in areas that would be eroded or covered in sargassum, we remove those clutches and bury them in the artificial hatcheries. We ran a little test of them last year and saw very successful hatchling emergence rates. It was pretty similar to what we would see on a clear beach, just about a 60% to 70% success rate.”

The odds are stacked against leatherback turtles hatchlings, with only one in 1,000 ever making it to adulthood, as they struggle against on-shore and in-water predators, along with harsh weather conditions and a lack of food. The effects of climate change and other human impacts further erode these odds.

Oftentimes, when staff conduct their overnight patrols, they come across turtles ensnared in nets and pierced by hooks.

“We encountered a turtle that had a hook from a fishing line lodged into her left shoulder, and the line was actually running into her mouth,” Wilson said. “So it’s possible that there was another hook inside of her mouth that we couldn’t get out.”

These grisly sightings are the result of bycatch — the unintended but devastating impact of fishing gear interfering with species not meant to be caught. Trinidad has no meaningful protected marine areas, meaning all of its waters can be exploited by fishermen. As a result, bycatch has become the biggest threat facing turtles. Nature Seekers has advocated for fishers to reduce their trawling net from 100 feet to 50 feet to prevent accidental collisions with turtles and other species that swim lower in the water.

“The thought process behind the bigger nets is that fishers think they catch more fish with them, but our project showed that because they are targeting species that live within the upper 50 feet of the water, if they reduced the size of their nets, they would essentially capture the same amount of fish that they would catch with the bigger nets,” said Kyle Mitchell, systems administrator for Nature Seekers. “And it would also reduce the amount of turtles they catch. If they’re catching fewer turtles, it means they have less downtime dealing with a turtle becoming entangled in their nets because they wouldn’t have to repair them as often.”

This sort of practical, community-based problem-solving is evident throughout Nature Seekers programs. When pollution washes up on shore, Nature Seekers works with local artisans to repurpose the waste into jewelry and other goods that tourists can buy. Once a year, the organization hosts a community beach clean-up to do a deep clean of the sand right before the nesting season. The educational tours it provides to tourists create an international coalition of advocates and important jobs for locals.

But as the climate and biodiversity crisis worsens, Nature Seekers needs government support as well. Marine protected areas, enforcement measures to limit bycatch, and increased funding for conservation are necessary to protect leatherback turtles. More broadly, governments worldwide need to invest in climate action to prevent temperatures from catastrophically rising and threatening the very existence of marine life.

“Our conservation is really a shared resource,” Wilson said. “This is one of the last strongholds for this leatherback species known as the North Western Atlantic population. The work that we do here directly impacts the entire population.”

Credits

Brendan Delzin.

Topics

Article written by

Joe McCarthy

Joe McCarthy is a writer based in Brooklyn who specializes in global politics, climate action, and pop culture.

Related

articles

Africa, Project

Inside the Fight to Protect Gambian Artisanal Fishermen and Biodiversity From Industrialized Fishing

News, Project, South America

Age of Union Announces USD $287,000 Commitment to The Juma Institute for New Knowledge Centre and Amazon Rainforest Protection

Project

More articles

News

Age of Union Marks 4 Years of Global Conservation Wins As COP30 Commences in Brazil

News, Other

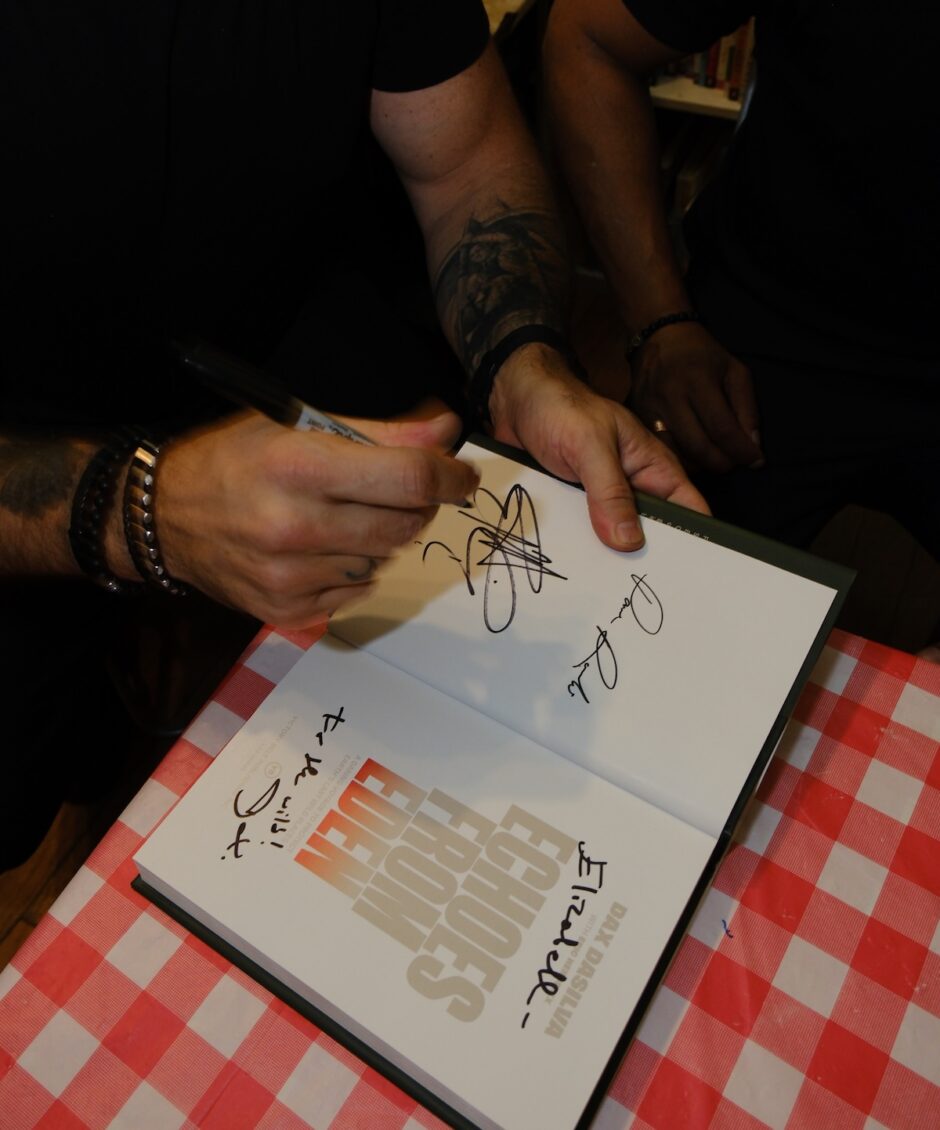

‘Echoes from Eden’ Book Tour Connects Readers to Urgent Stories of Conservation

Explainer, South America

In the Amazon, Gold Mining Leaves a Toxic Trail

America, Asia, News

What More Intense Wildfire Seasons Mean For People and the Planet

Film